Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Early Buoyage

- Trinity House Founded

- Collision Regulations and Ship Lighting: 1840s

- Taking Stock: The 1861 Royal Commission

- British Uniform Buoyage: The 1882 Trinity House Royal Conference

- Attempts at Worldwide Standards: 1889 & 1912

- The Problem of Lighting

- Pre World War Two British and European Systems

- Inter-War Attempt at a Common Standard: 1936

- Post World War Two, Britain changes sides

- The Varne Disaster

- Progress: Captain Bury takes the Chair

- A Unified System, of a Sort

The earliest aid to navigation must have been a withie planted in the mud but the floating buoy would have been the next. Such navigation aids have existed for centuries. Different methods of marking them developed causing confusion: from the 1800s onwards. Growing trade, steamships, ship and buoy lighting technology increased the problem: it remained unresolved, due to politics and war, until the late twentieth century.

Introduction

For centuries, navigation buoys have helped mariners avoid hazards and inform them of their position. The requirements of a floating barrel, chain or rope, and a stone sinker have been available since antiquity.1 For chains, see ‘Caesar • Gallic War—Book III’. For Cooperage,2 see Wikipedia Cooper (profession).

Shape, colour and topmark were the first characteristics used to differentiate buoys: authorities made independent choices, and so, for centuries, contradictory systems, both nationally and internationally, confused Mariners. There were many attempts in the late nineteenth, and first half of the twentieth century to achieve a common system but little success. Some of the proposals now seem perverse.

There must have been systems in the Eastern world but these are not discussed, nor are fixed navigation marks such as lighthouses, beacons or lighthouses.

We have used the simple, elegant IALA system since the 1980s. It has six types of buoy: Lateral, port, and starboard; Cardinals; Safe Water; Isolated Danger; Special Marks; and, since 2006, Wreck marks. Other than the colour difference between systems A and B, the scheme is consistent Worldwide.

So, how did the IALA develop; what preceded it in Britain; what logic underlies it, and what were the key developments along the way?

Early Buoyage

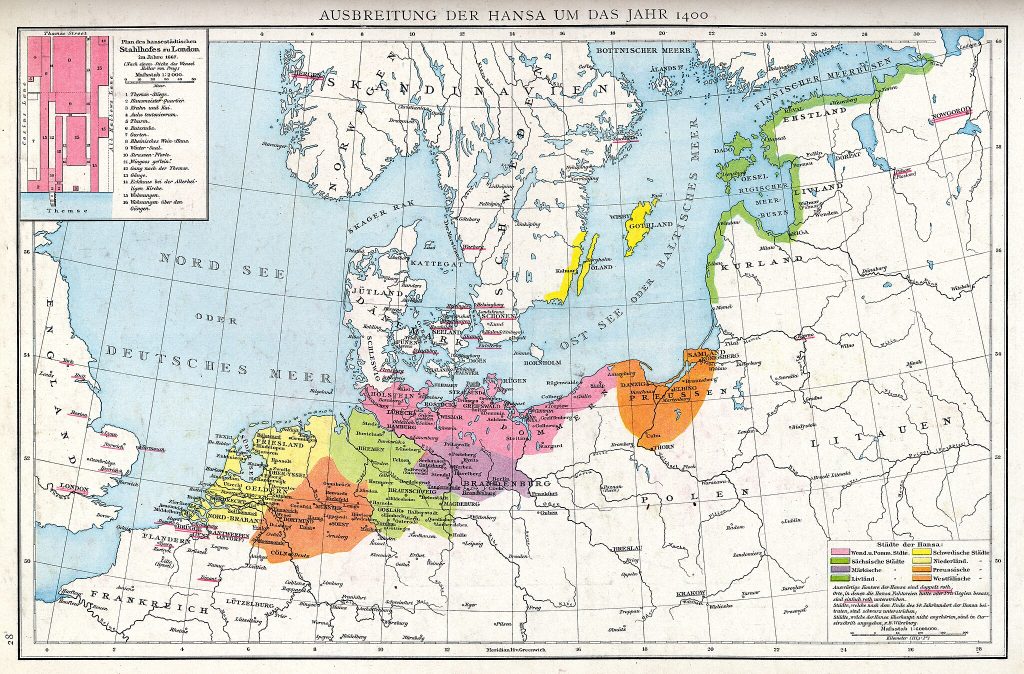

In the Western World, the practice of placing buoys can be traced to the Hanseatic League which traded across the Baltic and North Sea from the eleventh century.

The Low Countries have similarities to England’s East Coast with sandbanks and tidal streams. The Baltic, however, has negligible tides and many rocks and islands. Britain had few buoys until the nineteenth century and most likely absorbed some of the ideas from ports around the Wash3Hanseatic League and King’s Lynn with Hanseatic links as well as Europe.

Droysen/Andrée, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

probably found in Deben

To aid navigation, beacons, perches (withies), and buoys, known as ‘tonnen’ or ‘seetonnen’, were laid. The buoys would have been either barrels or conical wooden casks attached by iron chains to sinkers. There is a small example of this type at Woodbridge Museum although its origin is unknown. Cooperage techniques were used in their construction, they were often painted with pitch and so were black. Later in Europe, white was used for port but soon became fouled. Chained at the apex, they would have floated on their side, as depicted on old charts. Sometimes, top marks or flags were used and the name or number was painted on the circular face. In time, conical versions, or nuns, were developed allowing more discrimination.

Another name for the ‘tonnen’ was the Dutch or French ‘boeie’. It was this the English adopted. It can be pronounced as ‘boy’, or in the American style as ‘buoy’. Perhaps both are wrong as it may well have been pronounced ‘bwoy‘ in the early nineteenth century4Pronounciation of buoy – see Benjamin Humphrey Smart, A Practical Grammar of English Pronunciation: On Plain and Recognized Principles, Calculated to Assist in Removing Every Objectionable Peculiarity of Utterance Arising from Either Foreign, Provincial, Or Vulgar Habits, Or from a Defective Use of the Organs of Speech … : Together with Directions to Persons Who Stammer in Their Speech : Comprehending Some New Ideas Relative to English Prosody (John Richardson … and J. Johnson and Company, 1810).. . The word ‘tonne’ for barrel lives on in tons and tonnage.

Deutsch Wikipedia

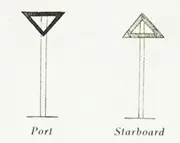

In Europe, the practice developed of marking channels with ‘brooms’ of birch twigs pointing down to the north and up to the south, although there does not seem to have been complete consistency in whether they indicated safe water or a hazard. This began the north point-up convention for the cones used on beacons and cardinals today. It also was generally associated with starboard marks.

from Meesum’s Rivers and Creeks

Tree trunks were commonly used as ‘spar’ type buoys, in the Baltic and United States where timber was plentiful. In these cool climes, the marks were often removed in Winter.

Trinity House Founded

Hull had its own Trinity House from 1369, Henry VIII founded the Trinity House in 1514 which was responsible for some areas, including the Thames Estuary and Bristol Channel. The number of buoys in the Estuary grew slowly, reaching only sixteen by 16845IALA AISM. ‘A History of Floating Aids to Navigation by Adrian H Wilkins’. and a ‘buoy boat’ was not commissioned until 1742. Apart from Hull’s Trinity House, Scotland had the Northern Lighthouse Board, Ireland its Ballast Board6Ballast Board became Irish Lights and the Mersey its authority.

Eighteenth Century

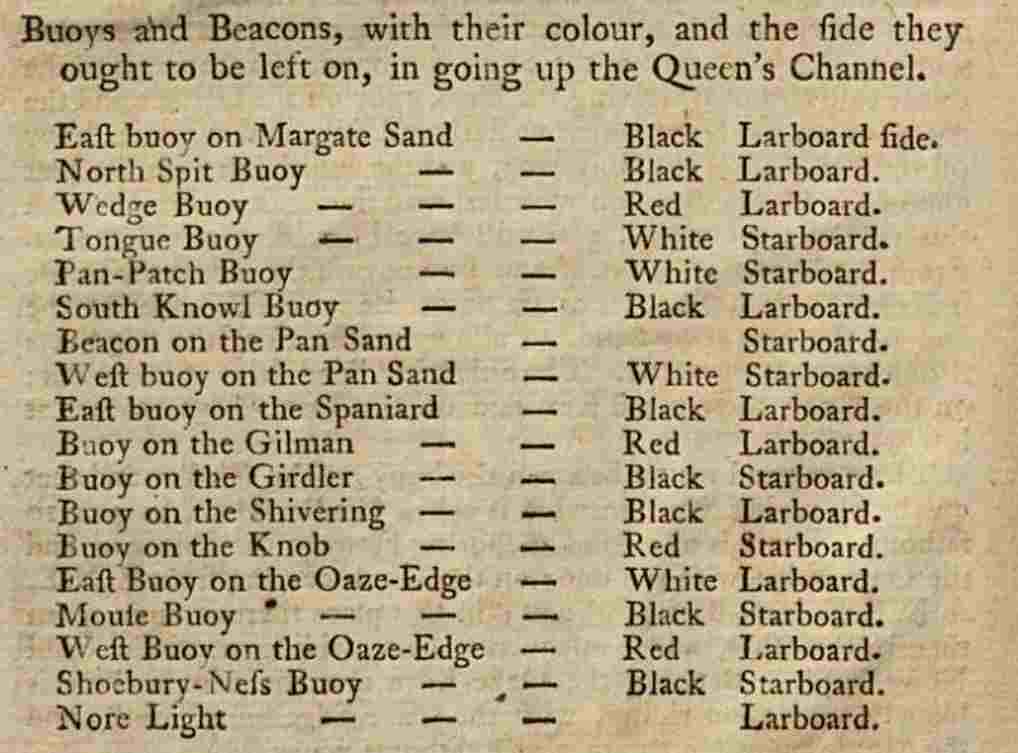

The 1787 Coasters Companion shows a variety of marks in the Thames Estuary with black, red and white, being assigned to port or starboard, seemingly at random. There was no direction of buoyage.

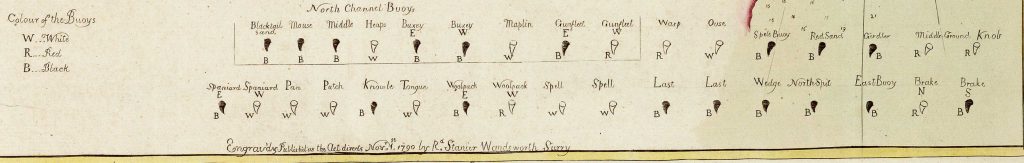

The 1790 Chart shows about thirty buoys in the Thames Estuary, as described above. White was hard to spot. None were lit at this time although there were some lightships.

Nearby Dunkirk laid black/starboard and white/port channel buoys in 1776.

Early Nineteenth Century

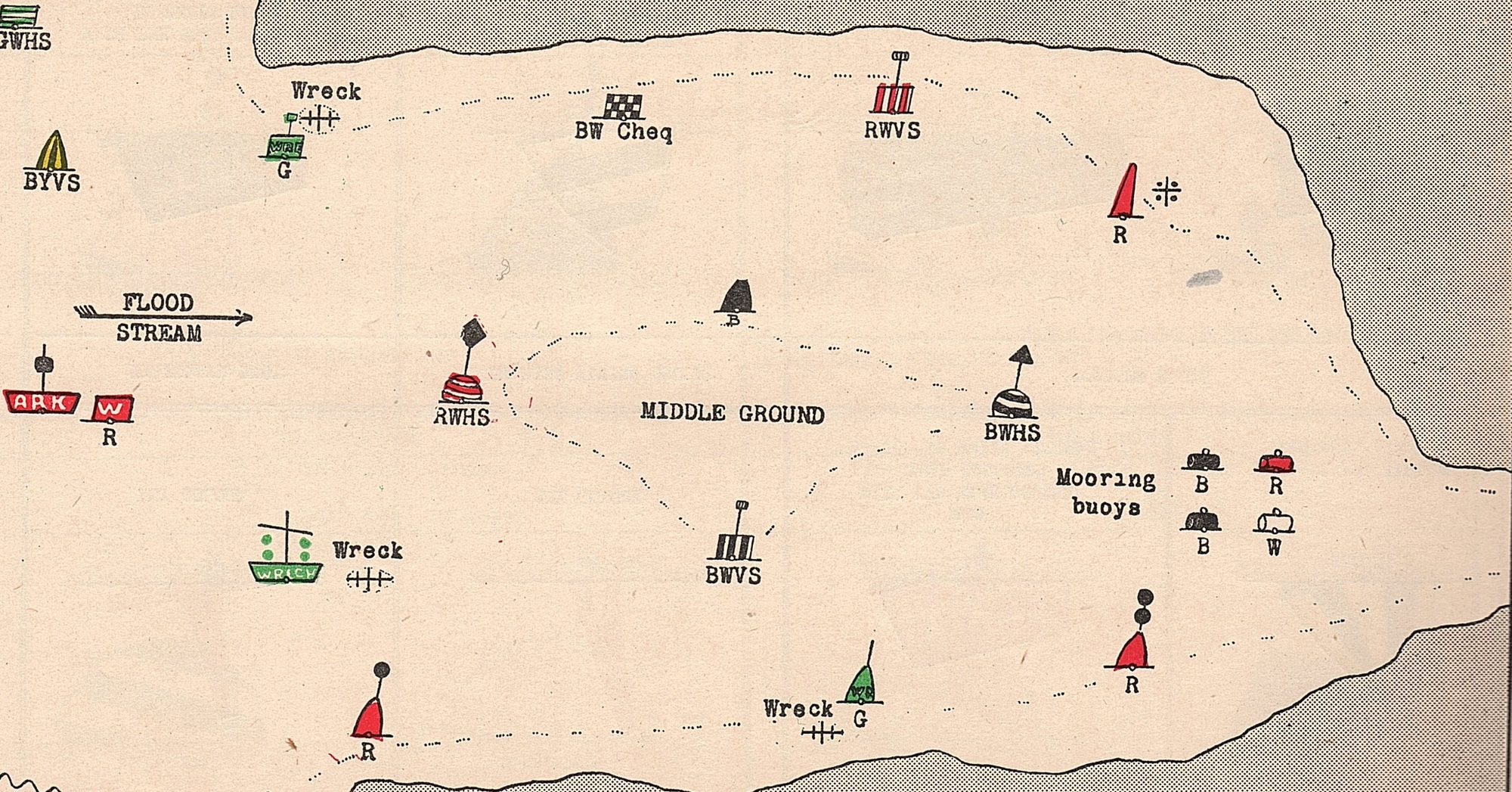

An extract from an 1845 chart of the Estuary shows several styles. They were deployed such that, if a rough location was known, the buoy would be sufficiently distinctive for identification from the pilot7See the 1844 Coasters Guide where buoys are learned by rote.The 1847 Sailing directions for the river Thames, from London enable the navigator to plan a route buoy to buoy..

Buoyage of Liverpool and the United States

Liverpool was Britain’s gateway to the west and, with the industrial revolution forging ahead, traffic was growing rapidly. In the early 1800s8The New British Channel Pilot. Containing Sailing Directions from London and Yarmouth to Liverpool, and from Ostend to Brest. Also for the Coast of Ireland, from Dublin to Galway Bay … The Whole Connected, Arranged and Improved by William Heather. 4th Ed, Liverpool had a system of cones to starboard and casks to port.

Lt Henry Mangles Denham9Henry Mangles Denham and A Naval Biographical Dictionary/Denham, Henry Mangles who had previously surveyed the Channel Islands and Coasts of France, was sent to survey the port in 1833 and made recommendations for the buoying of the channels101839 British Channel Pilot – p118 Liverpool – The Buoys in the channels are so arranged, that on entering, those painted red are to be left on the starboard side, and those painted black on the larboard. Buoys striped black and white, are laid upon intervening banks or flats. Superior can- buoys with perches are placed at the elbows or turning points of the principal channels. Each buoy bears the initial of the channel it occupies; thus , F , signifies Formby Channel; C , Crosby Channel ; H. F , Half tide Swashway ; N , New Channel; H , Horse Channel ; R , Rock Channel ; H. E. , Helbre Swash; B , Beggar’s Patch ; L. Hoyle Lake ; & c . The buoys are likewise numbered in rotation , No. 1 denoting the outer or seaward buoy of its channel the letter indicates.. By 1839 he had set the buoyage to be starboard/cones/red and port/cans/black. He also set buoys to mark middle ground buoys at the end and sides. Channel buoys were named and numbered.

His work on the Mersey, which was influenced by the French11The French system from 1839 was red cans to starboard and black cones to port with naming and numbering, there were various striped buoys and topmarks. It is unclear when this started., formed the basis for other systems. As the United States carried out much of its trade via Liverpool it also adopted the ‘red, right returning’ system in 185112The US in any case mostly used spar or cask buoys.. Scotland adopted the plan in 1857. This was the critical choice that led to the division into IALA A and B.

Collision Regulations and Ship Lighting: 1840s

As the Industrial Revolution progressed in the nineteenth century, not only was sea traffic growing with trade but the age of the steamer had dawned. Britannia ruled the waves. Collisions, wrecks and groundings were commonplace.

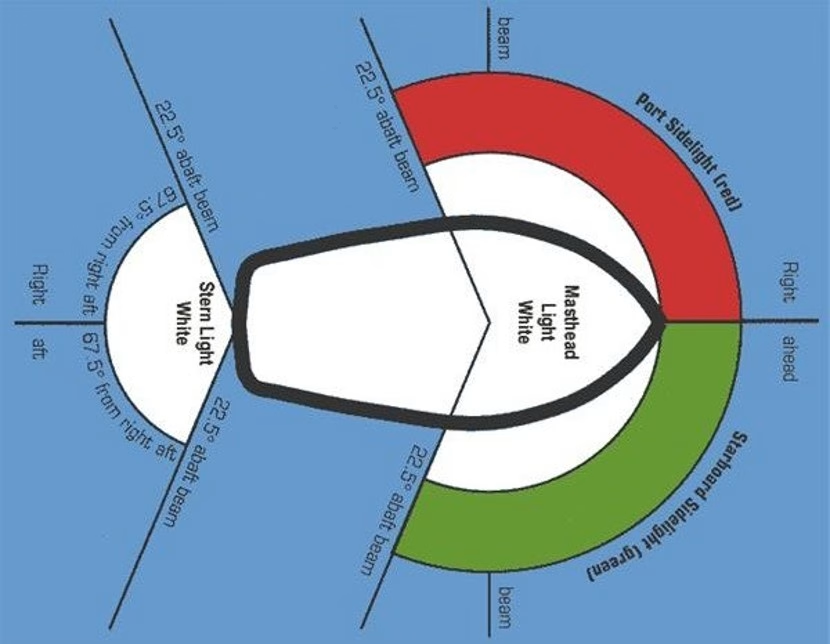

The 1840s saw the introduction of British Collision Regulations13Colregs see Bahr, Rudiger. ‘The Development of Regulations for Preventing Collisions in Inland, Inshore, and Open Waters of the UK during the First Half of the Nineteenth Century’. Thesis, University of St Andrews, 1998. https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/handle/10023/14084. and then, in 1848, the Admiralty required steamers to display lights, in the form we know today, red to port, green to starboard.

As ships conventionally passed port to port and red meant danger, this was logical, at least in Western culture. These regulations remained, with small alterations, to the present day.

Taking Stock: The 1861 Royal Commission

In the mid-nineteenth century, marine navigation was chaotic: buoy colours and shapes were not standardised and they were unlit. So, in 1861, the Royal Commission was formed on the state of British lights and buoys. Trinity House, the Lighthouse Authority for England, managed over three hundred buoys in England. However, across the U.K. management of buoys was divided between three or four Lighthouse authorities, the Admiralty, and local authorities. Each operated its own, sometimes conflicting, system. There was not even consistent vocabulary for describing buoy shapes: cones, nuns, spirals etc..

So, about 140 different organisations were managing around 1100 buoys in the United Kingdom: 55% were managed by Local Authorities; Liverpool and the Clyde being the largest. Trinity House had a plan of black or red cones to starboard, and striped or chequered cans to port although only used this on new buoys

1861 Extracts from the Report of Her Britanic Majesty’s Commissioners, appointed to inquire into the Condition and Management of Lights, Buoys, and Beacons, Submitted March 5, 1861,; Liverpool14Liiverpool in the 1815 survey by George Thomas has cask buoys at key points15Liverpool Buoyage see page 130 Admiralty hydrography dept, Sailing Directions for the West Coast of England, West Coast of England Pilot. Admiralty Notices to Mariners, 1870. had adopted red cans to starboard, black cones to port for the Mersea, Scotland had a similar scheme although Hull16Hull- see 1861 Report of Her Britanic Majesty’s Commissioners, appointed to inquire into the Condition and Management of Lights, Buoys, and Beacons, Submitted March 5, 1861 page 319 – XXVII. All the buoys on the south side of the Humber are coloured red, with a horizontal white stripe, and numbered 1 to 12, commencing with the sand hale buoy, and terminating with the westernmost buoy on the upper middle, opposite the town of Hull. The buoys on the north side are all black, and numbered 1 to 12, commencing with the outer binks buoy, and terminating with the upper hebbles buoy. The buoys on the middle sands or shoals in the lower part of the Humber are all chequered black and white. The hook buoy on the lower middle is painted white, and marked “book middle.” had the opposite, and so on. had black to starboard, red to port and chequered B/W middle grounds

A ‘Proposed Uniform Code’ based on the Liverpool system was submitted to the Commission by Captain E.J. Bedford although this does not appear to have been adopted, it was claimed to be similar to the French system171874 Sailing Directions for the English Channel: The south coast of England, and general directions for the navigation of the Channel. The north coast of France, Parts 1-2 pp236 – BEACONS AND BUOYS . The following is the system of Buoys and Beacons on the coast of France : – When entering a channel from sea all buoys and beacons painted red with white band near the summit must be left to starboard , and those painted black to port . That part of the beacon which is below the level of high water , and all warping buoys are coloured white . The small rocky heads in frequented channels are coloured in the same way as the beacons , when they have a surface sufficiently conspicuous . Each beacon or buoy has upon it in full length or in abbreviation , the name of the danger it is meant to distinguish , likewise its number , commencing from sea- ward , and thus showing its numerical order in the same channel . The even numbers are on the red buoys , and the odd numbers on the black buoys ; the buoys and beacons coloured red , with black horizontal bands are named , not numbered .. By 1890 Liverpool conformed to the Uniform System181891 Sailing Directions for the West Coast of England – BUOYAGE . – The uniform system is adopted in buoying the several channels to the Mersey , and is such that , coming upon a buoy in the night the seaman may know by its shape on which side of the channel it is situated . An uniform system with respect to colour is likewise maintained as far as circumstances will allow . Thus , when inward bound , conical buoys are to be left on the starboard hand , can buoys on the port hand , and spherical buoys on either hand ; the conical buoys are painted red , can buoys black , and spherical buoys with horizontal stripes . On the buoys of every channel are painted the initial letter of the channel , with a number , the numerals being arranged in consecutive order , reckoning from seaward ; thus a conical buoy , marked Q. 1 , or a can buoy Q. 1 , denotes , respectively , the outer buoy on either side of Queen’s channel , the next buoys inward being marked Q. 2 , and so on for other channels . Fairway buoys bear the initial letter of their channel , and ” Fy . , ” and have distinct characteristics of form and colour ..

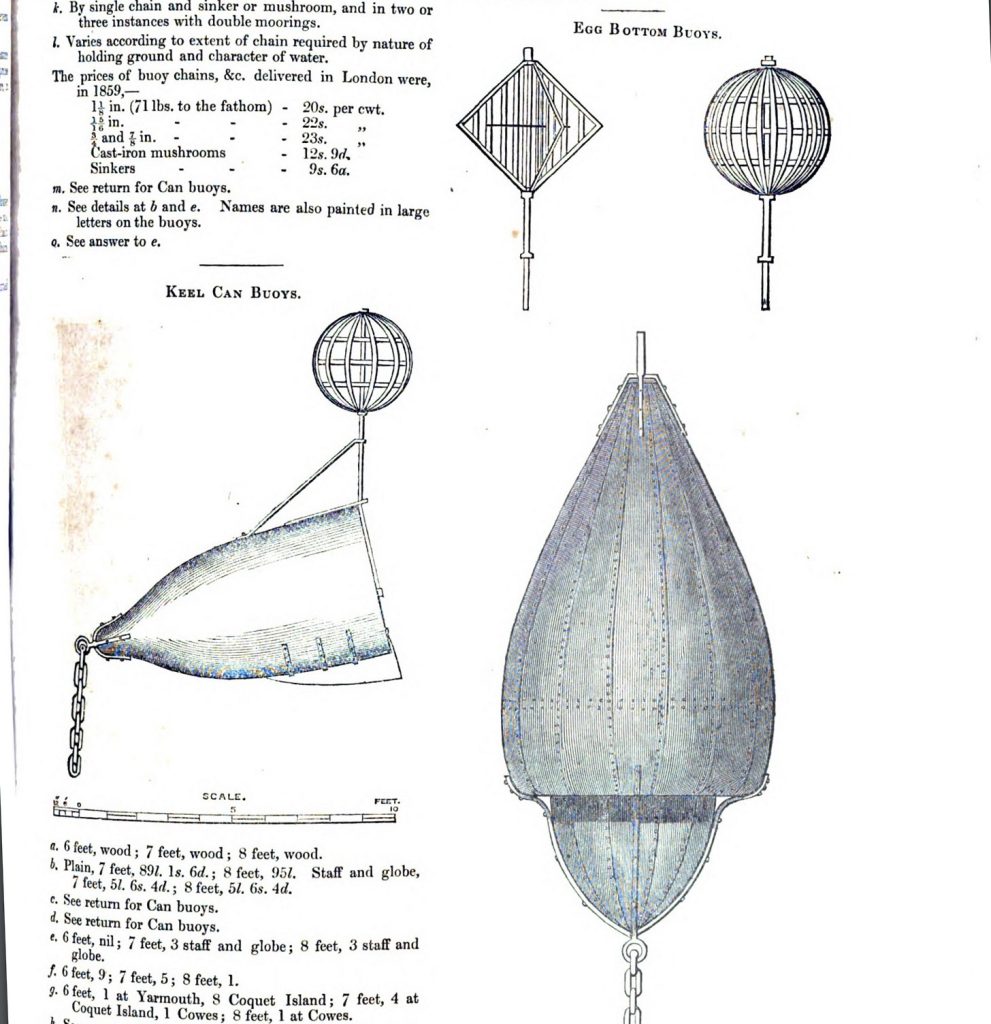

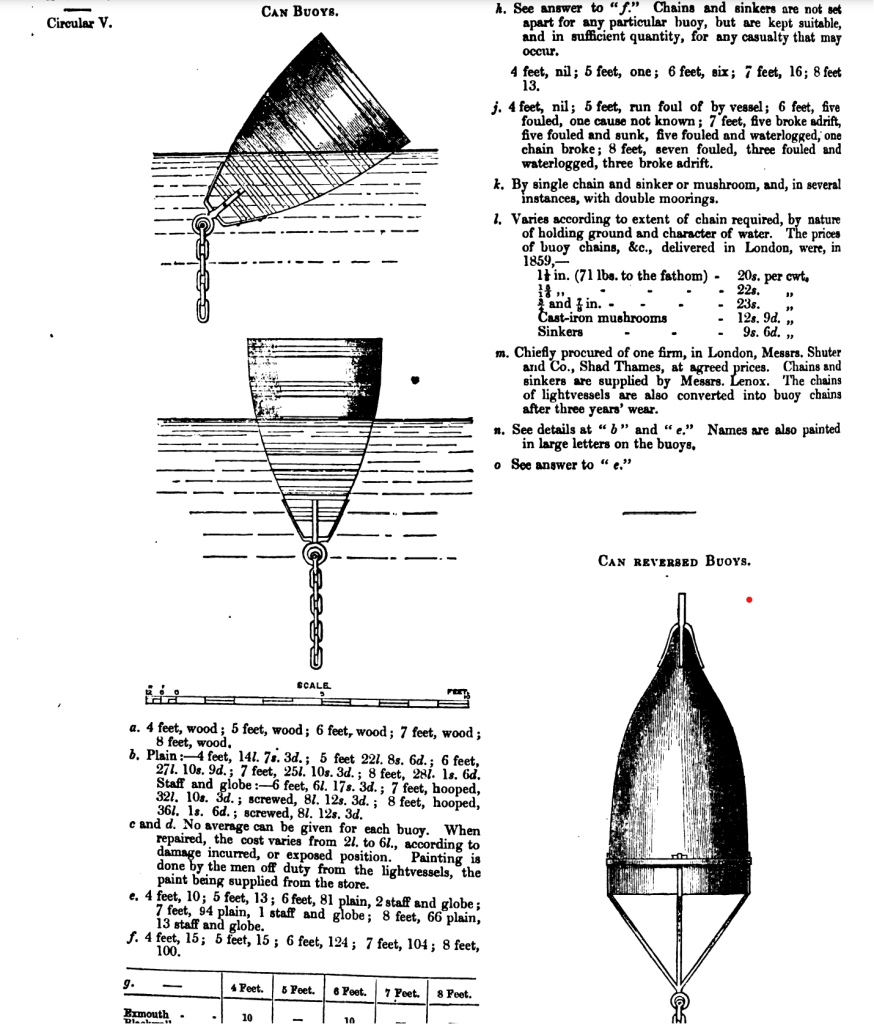

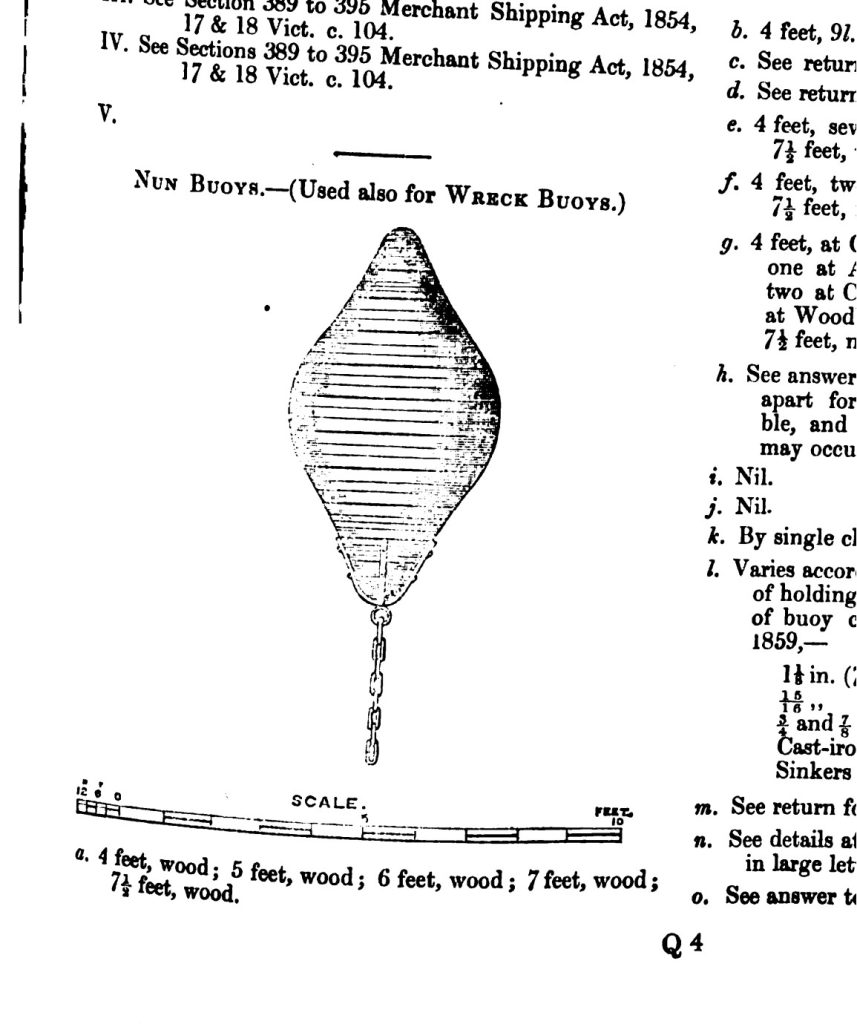

A key development was the introduction of buoys made of iron. This was the enabler for larger, more durable marks and greatly increased the range of shapes available. It was also a necessary precursor to the storage of fuel that would needed for soon for lighted buoys.

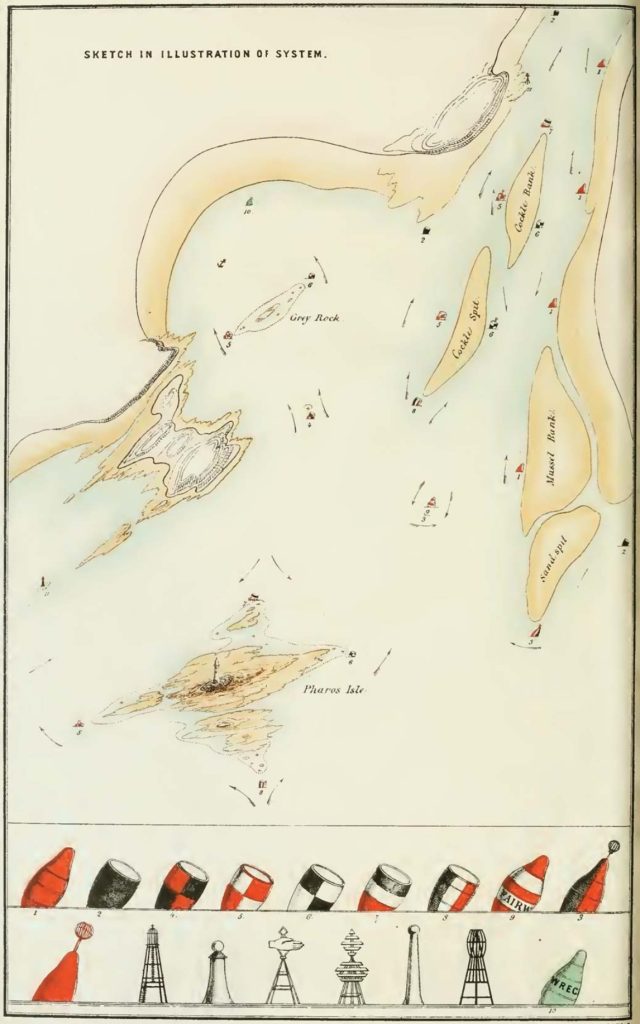

The images, from an 1861 report19See Charles Babbage and Lighting, not implemented but interesting. show some of the types in use, buoys could be cans or cones in black, red or white, with horizontal and vertical stripes and with or without various top marks:

Bell buoys appeared in 1860 and whistles twenty years later along with the first lights.

By 1877 the Ovens buoy on the Thames was trialled with the Pintsch gas lighting system20Pintsch gas lighting system. Soon these could run for over three weeks unattended and were deployed in key locations.

It took two more decades to act on the Commission’s findings although the report is a valuable historical resource.

The 1882 Trinity House Royal Conference

Twenty years passed before the problem was addressed by the Royal Conference at Trinity House in 1882, chaired by the Duke of Edinburgh.

British Uniform Buoyage:

This produced the ‘Uniform System of Buoyage’211883 Nautical Magazine VOLUME LII.-No. VIII. AUGUST , 1883 . see page 573 for the UNIFORM SYSTEM OF BUOYAGE.. Shape rather than buoy colour was the key characteristic with colours optional. Cones to be to starboard, all of one solid, unspecified, colour and cans to port in a different colour, possibly patterned. The top marks could be a globe, can, diamond and triangle. The direction of buoyage was the flood and spherical middle ground buoys were included as well as green wreck marks. This scheme was gradually adopted, and by 1890 Liverpool conformed to the Uniform System. It was, however, liberal enough to allow most authorities to adopt with minimal change. By then, the Thames Estuary had 185 buoys including eight gas-lit buoys introduced a decade earlier.

Middle Ground Buoys

The term ‘middle-ground’ had been used since at least the seventeenth Century22See A Description & Plat of the Sea-Coasts of England, 1653 to describe a bank with a channel on either side. Middle ground buoys appeared in the Bristol Channel between 1839 and 186823See the 1839 Pilot and 1868 Bristol Channel Chart. Middle grounds were in Bedford’s proposal, were used in Liverpool, , the Thames Estuary between 1852241852 A new chart of the River Thames inc. Harwich and 1907 Reynold’s new chart of the Thames Estuary see Oaze & Girdler. and there was one at Hull in 1870.

This scheme was largely adopted and endured, more or less, until 1977, nearly a century. As technology made it possible to place buoys further out to sea, ambiguity arose with the flood-oriented laterals and middle-grounds.

Attempts at Worldwide Standards: 1889 & 1912

Britain was to be, until the 1960s, the pre-eminent maritime power and much of the Empire would follow her lead: also, France and North America were broadly consistent. European countries had a variety of systems with some Baltic states having a compass based system.

Following the 1861 Royal Conference, there were attempts over the next sixty years to reach a worldwide agreement on buoyage. The main ones were Washington in 1889, St Petersburg in 1912 and Geneva in 1936. These had few tangible results.

1889 Washington International Marine Conference

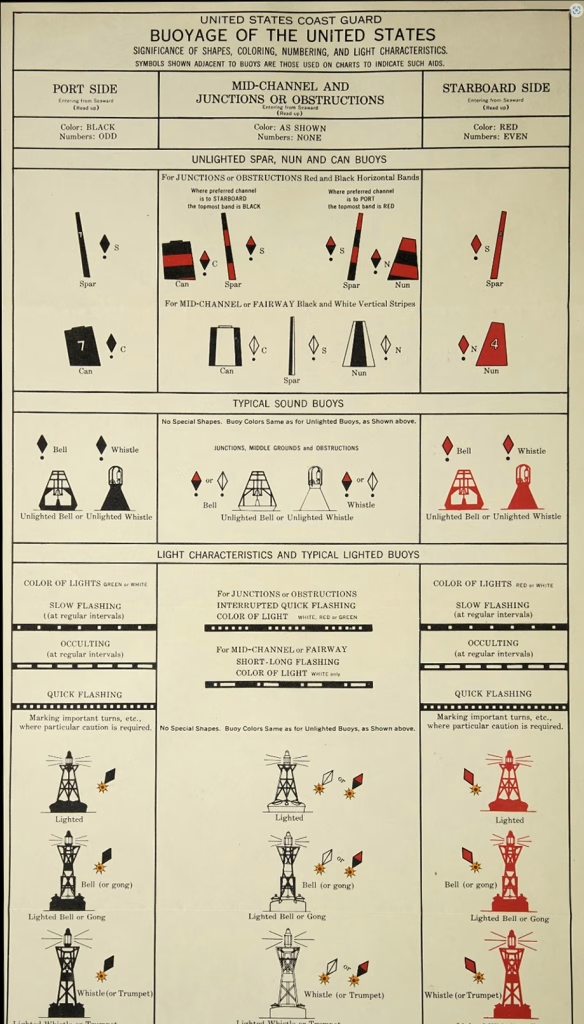

This conference aimed to build upon the Royal Conference and achieve some international agreement. It took the stance that buoys should be distinguished by colour and number, rather than shape, partly on the basis that colour was easier to change. It recommended red, ideally conical, to starboard and port, ideally can, black or multicolour. Middle-ground buoys were to be horizontal stripes. The U.S., France and Spain adopted this scheme and it was not inconsistent with the British scheme, although the British involvement does not appear to have been wholehearted. North America was to retain this scheme throughout. The conference was wide-ranging and included lighting, signals, collision regulations, bearings and safety at sea. There was an attempt to agree on a compass, or cardinal, system but judging by the systems in use in the Baltic in the early twentieth century this was not widely adopted.

At this point, it should not have been difficult to agree on red cones to starboard and black cans to port but the chance was lost.

1912 St Petersburg Conference

This strange conference was called by Russia and France with the invitation to the U.S. going out at the last minute, and none to the U.K. and Canada. It reversed the Washington system with red cones to port and black cans to starboard. However, only three countries adopted the resolutions and this affair must have caused more problems than it solved. The French did not implement this scheme despite being a key player.

Lighting Creates a Problem

By the 1910s, there were many lit buoys which could be confused with ships’ lights as not all flashed. It was also the case that, despite red generally being used for starboard, harbour lights in Europe mostly adopted the red-to-port convention.

Around this time there was a major advance in buoy lighting with Gustaf Dalén’s acetylene system. This produced a far brighter light and was accompanied by an occulting mechanism and daylight sensor. Dalen was awarded a Nobel Physics Prize for this work: Albert Einstein had to wait. Dalen’s system was still in use in the 1980s.

Pre World War Two British and European Systems

British Uniform Buoyage

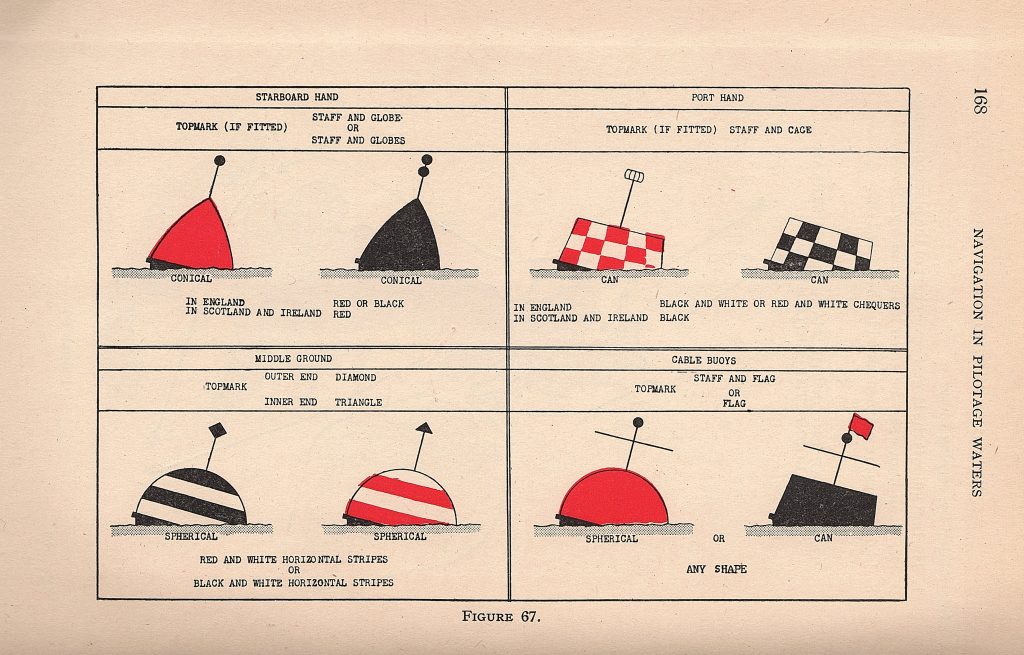

The pre-war British system dated back to 1882. Trinity House emphasised buoy shape: single colour red or black cones to starboard, parti (multi) colour cans to port: the emphasis was on shape and topmark, not colour. Scotland and Liverpool were more consistent in having red cones to starboard. 25See United States Hydrographic Office, British Islands Pilot: East Coasts of Scotland and England (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1915) page 34 – Coloring of buoys . – In carrying out the above uniform system on the east coast of England the colors adopted by the Trinity Houses of London and Newcastle are whole colors on the starboard hand and parti – colors on the port hand ; in Scotland starboard hand buoys are painted red and port hand buoys black. This system was to remain in place, with some swapping of red and black, until 1977. The key elements were:

Lateral and Middle-Ground buoys

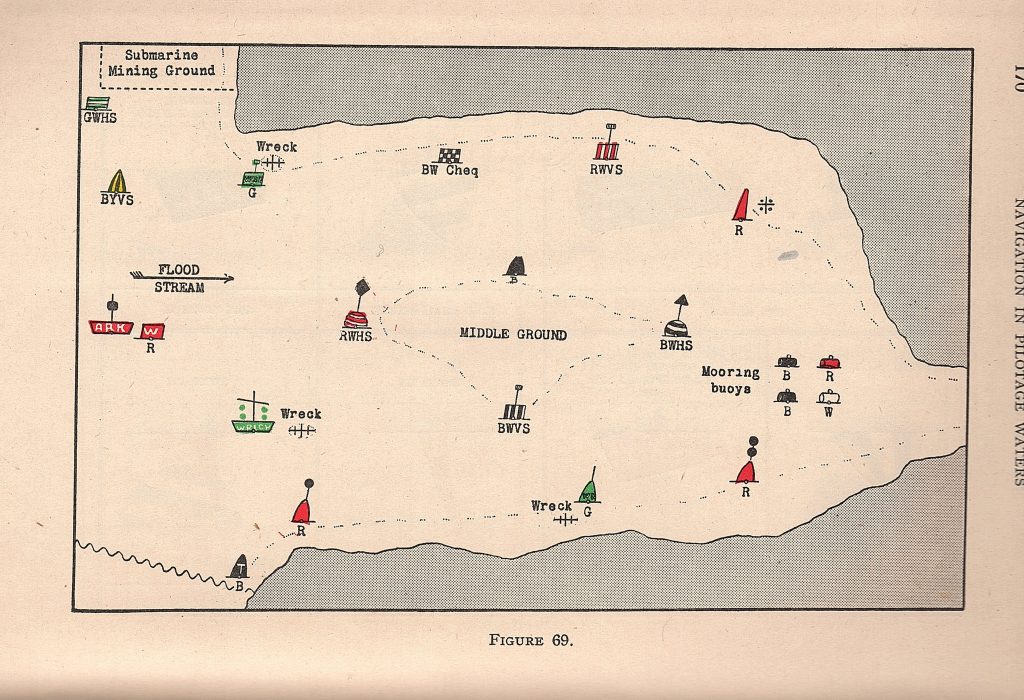

Spherical, striped, middle-ground buoys were used to mark sandbanks, often with side laterals.

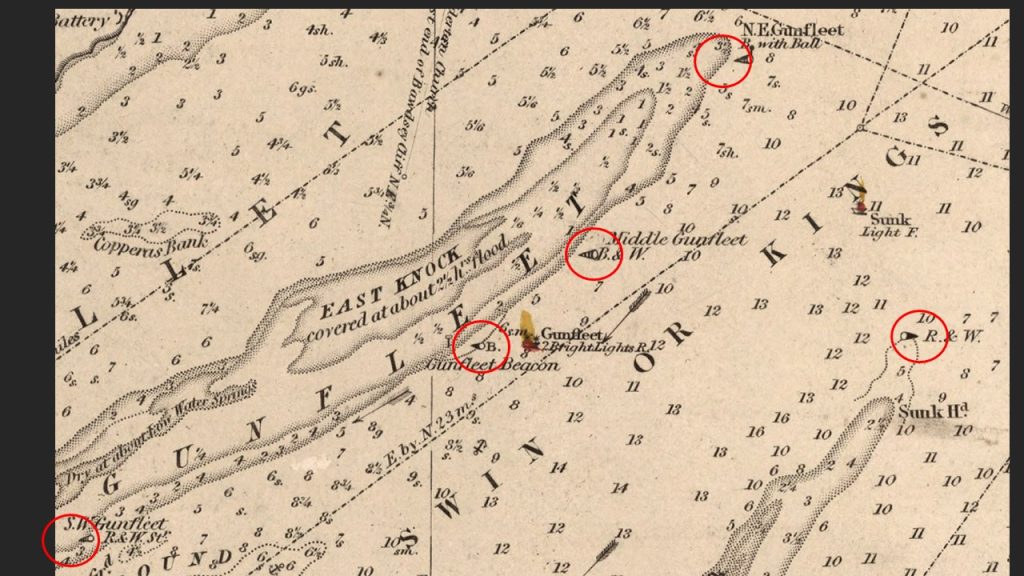

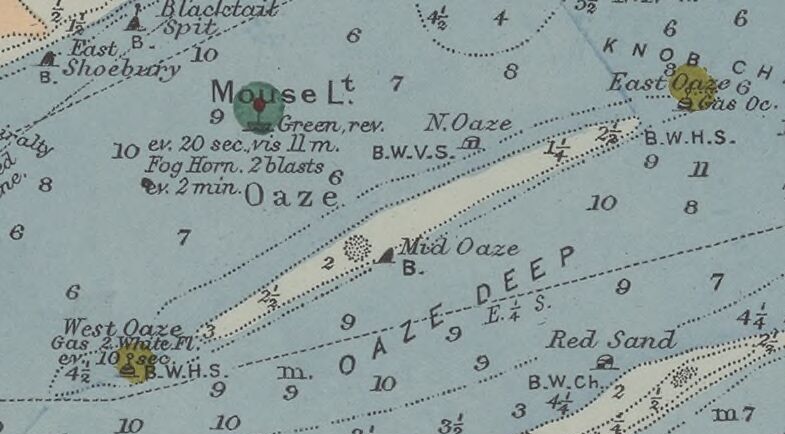

The extract from the 1907 Reynolds Chart of the Oaze Bank shows middle-grounds deployed. They were supposed to mark the inner and outer extremities but, in this case, failed to differentiate. Note that they are gas-lit and occulting – the latest technology.

This chart shows, perhaps, two dozen gas-lit buoys in the southern part of the Estuary: only Whitaker and Knoll are gas-lit north of the Crouch. In England. There were still a few wooden buoys in place in the 1920s, before the Second World War, the main marks were:

European Systems

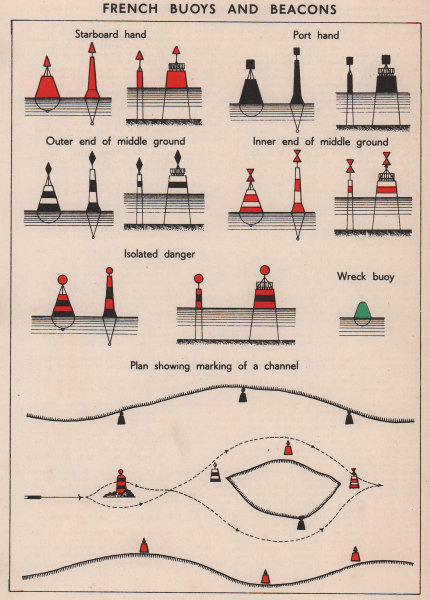

French buoys were similar to the British in the early twentieth century, note the familiar top marks:

The British, American and French systems did not use cardinals, preferring middle-ground marks: all had red to starboard, although England was less rigorous on colour.

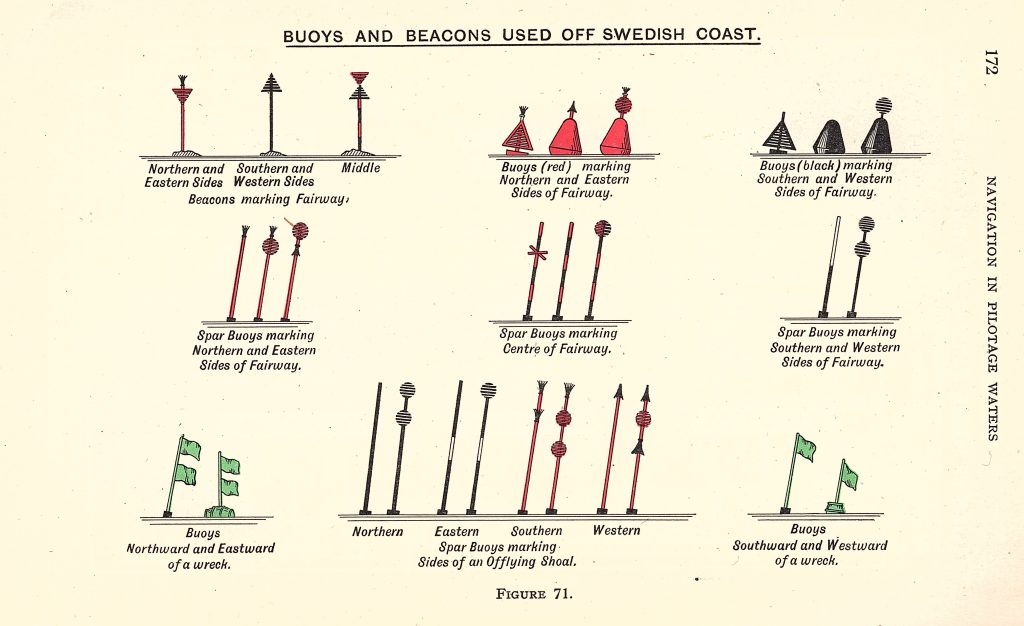

Baltic Cardinal Buoys

The lateral/cardinal systems used in the Baltic related to compass bearings and, some indicated the direction of the danger, not the safe water. The examples are from the 1930s. The emphasis was on compass bearing rather than flood stream, because of indefinite tides.

First, the Swedish version, which combines cardinals and laterals and looks daunting:

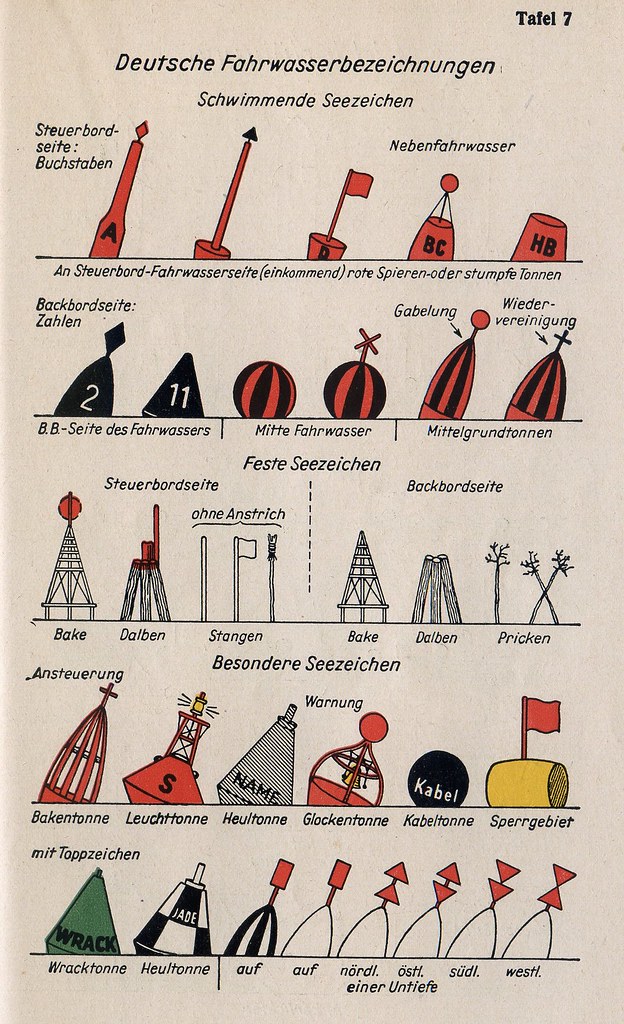

The German scheme was different and had laterals with red cans to starboard, and black cones to port, note the cardinal top marks which were to live on in the IALA system:

United States

Inter-War Attempt at a Common Standard: 1936

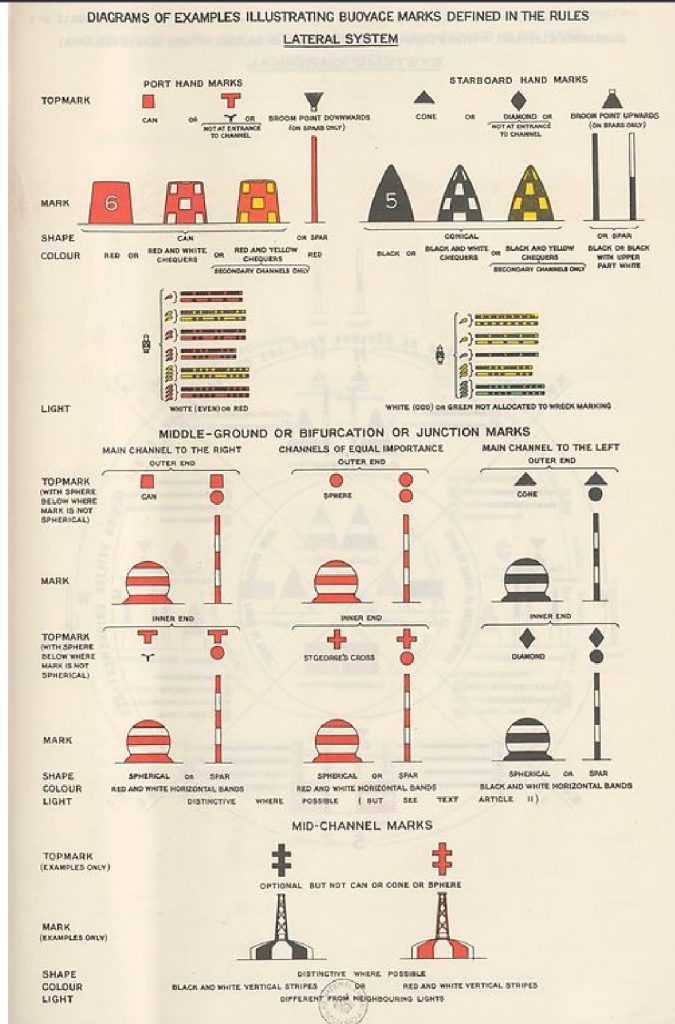

The League of Nations, created after the Great War, held Conferences to produce a Uniform System of Buoyage. This recommended red cans to port with red lights, even numbers, black cones to starboard, white lights and odd numbers. The upwards cone was standardised for starboard and square can for port top marks. Chequer patterns were included, perhaps for the British. The direction of buoyage was usually the flood stream.

The scheme had a complex set of top marks. The North and South cone shapes could be replaced by ‘brooms’ of twigs or branches as used in minor channels. Additionally, there were green marks for wrecks and middle-ground spherical buoys. The green light was reserved for wrecks and Cardinals were included. The many variations reflected the need to keep all parties satisfied.

The complex cardinal system could be confused with laterals and lacks the economy and clarity of the IALA scheme. The cardinal indicates the direction of the danger, not safe water261936 Geneva Cardinals – ‘The cardinal system is generally used to indicate dangers where the coast is flanked by numerous islands, rocks and shoals, as well as to indicate dangers in the open sea. In this system, the bearing (true) of the mark from the danger is indicated to the nearest cardinal point.’.

Britain’s acceptance was conditional on that of her North Sea neighbours and, although they had mostly accepted, Britain did not adopt the system. The U.S. did not ratify this noting that it would have to reverse the colours of over 22,000 buoys, approximately 40% of the World’s stock. The Uniform System conflicted with those of the UK, US, and France which was a recipe for failure although it had the characteristic that the buoy colours were almost the same way around as the ships’ lights.

The Second World War brought progress to a halt.

Post World War Two, Britain changes sides

The end of the War was an opportunity to update systems. In the U.K. and Europe, many buoys had been removed and maintenance ignored. Charts of the time show that the Second World War left many green wreck buoys around our coasts. They also show that there were inconsistencies: for example, by 1948 Harwich had black cones to starboard, and red cans port but the River Orwell had red cones to starboard and black cans to port. Lights to starboard were white, green was still used for wrecks. The use of middle-ground buoys was common, there were no cardinals. Around 1950 these colours were swapped to become consistent with the Uniform System of Buoyage: the change happened quickly in the Thames Estuary.

Of local interest is that, in 1950, six buoys were placed in the Waldringfield Fairway from Methersgate to the Rocks on the River Deben, these probably replaced the wooden beacons. New Trinity House rules were to change all channel markings to Black to Starboard, and Red to Port. Waldringfield adopted this scheme, the buoys being positioned by the appropriately named Mr Nunn, although Woodbridge declined, their buoys were recorded as being the other way around, which may have caused confusion at Methersgate27See Deben Beacons.

During the nineteen fifties and sixties, major advances in technology occurred. Steel had long replaced iron and there were trials of GRP and plastic for buoy bodies. There were major developments in lighting and electronic aids that provided yet more options for diversity. Many methods for powering buoy lighting, sound and electronics were tried from seawater batteries to radioactive isotopes.

The Varne Disaster

So, post-war, countries had adopted variants of the British or the League of Nations schemes. In general, however, everyone, more or less, carried on as they were. For example, Denmark had black to starboard, and white to port, while Holland and Belgium, had the opposite. There were inconsistencies of colour around Britain up to at least the 1950s. However, War intervened so confusion continued.

An IALA committee was established in 1967 to address the confusion. Although it agreed on ODAS boys and the marking of beaches little real progress was made. The US and Canada made it clear that they were not going to change their buoyage which was based on the 1892 Washington System. They had a simple lateral system with red to starboard and no cardinals.

On the night of January 11th 1971, the outbound tanker Texaco Caribbean collided with inbound cargo vessel Paracas near the Varne Bank. She exploded and broke in two, Paracas was damaged but eventually towed to port. The next night outward bound MV Brandenburg struck the wreck and soon foundered just two miles away. By late February many green wreck buoys had been laid and a ‘Wreck Light Ship’ put in place. Despite this another cargo vessel, the outward-bound Niki, struck the wreck and sank. All three wrecks had a considerable loss of life. It should be noted that, in this era, there was an optional traffic lane scheme but ships were free to sail wherever was convenient and there was no RADAR surveillance as there is today. The three incidents were a catalyst for the formalisation of the Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) within the Straits of Dover

Progress: Captain Bury takes the Chair

This emergency focussed the minds of the IALA committee but by 1973, there was still no agreement, although cardinals had been abandoned in an attempt to achieve unification. At this point, Captain John Bury was appointed to chair the committee. This problem had festered for over a century so a new approach was needed. He determined to cut losses and start from the first principles using logic and set the principle that buoys should convey their information on a pitch-black night. This implies the use of light colour and probably, rhythm.

Laterals

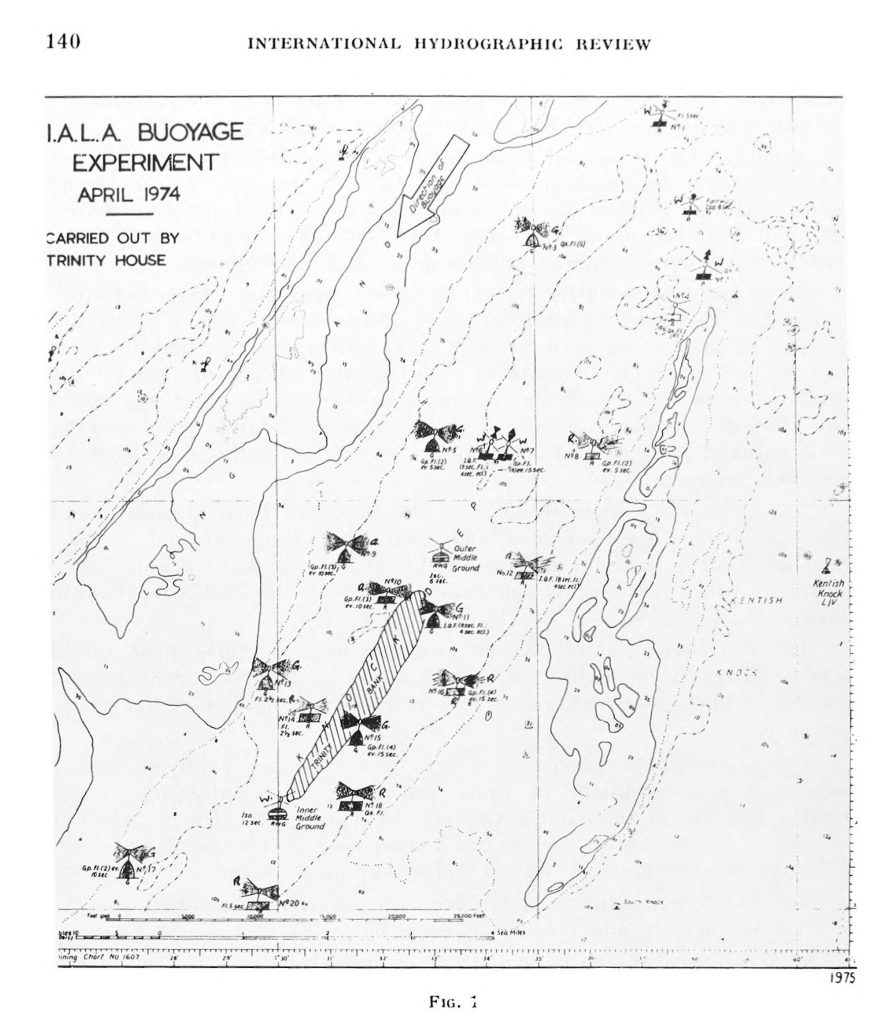

Bury adopted the principle that the lateral system should be oriented with a conventional direction of buoyage and not necessarily the flood tide which caused ambiguity. The colour and lighting of laterals were addressed by assigning red and green exclusively to them. The use of green solely for wrecks was seen as a waste of colour. Numbering was to be in the direction of buoyage with even or reds and odd on greens. All lights would flash, this had not been the case meaning that fixed and floating lights could be confused. The new lateral system was set up in 1974 as a trial in the Knock Deep and found satisfactory. Today trials are conducted East of Cork Sand from Harwich.

Specials

Larger tankers needed deep water channels, as at Southampton. These could not be marked unambiguously with laterals. Consequently, yellow marks with yellow lights were introduced as laterals. This enabled normal shipping to follow the usual reds and greens to leave the deep water clear.

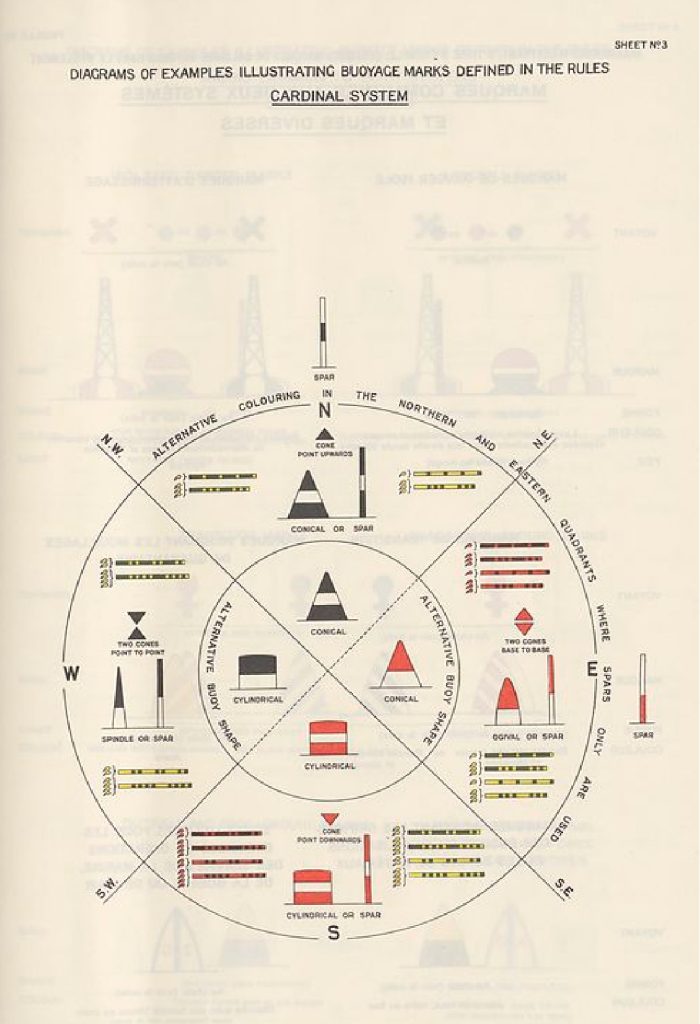

Middle Ground to Cardinal

At sea, an isolated lateral could be ambiguous. Middle Ground buoys failed the pitch-black night test as they were distinguished by their spherical shape so were abandoned in favour of cardinals. The development of the cardinal system was interesting. Various, inconsistent, systems had been used in the Baltic but indicated the bearing from the danger lay, not safe water. The German topmark system appears to have been co-opted. The Swedish system of cardinals was quite different. The 1937 Uniform System would have failed the pitch-black night test. Yellow was adopted to distinguish cardinals from laterals and the principle of operation was changed to indicate safe water not danger. It would be the responsibility of the navigator to recognise the special mark and assess the danger from a chart.

The cardinal lighting sequence was constrained by technology and arrived at as much by accident as design. To meet the pitch-black night test, distinctive colours or rhythms were needed. Three sequences for the cardinal directions, including VQ for North and Gp Fl(3) for S were proposed but the fourth sequence proved difficult to find. It was difficult to flash a definite number and long flashes were wasteful of gas. Eventually, the gas lighting technology was developed to produce up to eleven definite flashes and the sequence N-VQ, E- Gp Fl(6)+Long, S-3 and W-9 was established. At this point, somebody had an epiphany and realised that small changes would result in the clock face we now know. The Black/Yellow day colour system was then added, this simple, logical scheme provides redundancy for the top marks. It was sea-tested in the Baltic at night in a force seven and found to work well. The replacement of spherical middle ground buoys with pillar cardinals must have left many sphericals spare albeit some could be re-used as safe water marks.

Isolated and Safe Water

An Isolated Danger mark would only be used where the water was navigable all around, the chosen scheme is similar to the French version. A Safe Water mark would indicate safe water in a channel. These and cardinals used the white light in different sequences.

A Unified System, of a Sort

The IALA A system was agreed upon in 1977 and implemented at different speeds by the signatories with the U.K. being an early adopter, the new system is shown on a 1975 chart. The U.S. and Canada had been involved in the process and were soon to agree and adopt the similar IALA B system, with reversed red and green, in 1980. The Emergency Wreck Marking Buoy was introduced in 2005. Between 1977 and 2006 new dangers such as wrecks were marked by cardinal and special marks as green had been allocated to lateral marks.

The IALA A system of buoys has five basic shapes: can, cone, sphere, pillar and spar. There are six colours: Green, Red, Black, Yellow and Blue. The three basic patterns are solid, vertical stripes or horizontal stripes. To cap them, there are five top marks: Point up, Point down, Can, Sphere and X. Finally, lights can be green, red, yellow or blue with some sequence of flashing, no lights are fixed.

So, as should now be apparent, the system, which today seems so simple and logical, had a longer and more torturous development than one would think. Future developments are likely to be in the electronic, virtual realm: let us hope that we retain the physical buoys for many years to come.

Related

World War Two Air Sea Rescue Buoys or Floats

Notes

Sources

Examples from Charts & Pilots

- 1680s Greenvile collins Survey. One buoy at Harwich. One buoy in Humber. None Milford Haven. Three in Plymouth Sound. One at Yarmouth (Norfolk). Moray Firth, none. Fowey, none.

- 1790 The New and Complete Channel Pilot, Or Sailing Directions for Navigating the British Channele on the English and French Coasts, as Well on the South West and West Coasts of Ireland: Adapted to Sayer’s Charts of that Channel In the Month of Auguſt 1776, the Board of Admiralty of Dunkirk gave the following Notice to Navigators, Viz. – – – “In confideration of the advantages which navigation has reaped from the four Buoys placed to the Weſt of the Road of Dunkirk, according to the general information given in 1774, which gave notice that Navigators in entering the Road, through the Weft Paſſage, would meet with the Firſ; Black Buoy, on the Eaſt Point of the Bank, called The Geere, at the Entrance of the Road, which they are to leave on the Starboard Side. “A Second, likewiſe Black, at the Point of the Bank, named Skau, or Splinter, oppoſite to Great Mardyck, which they leave alſo on the Starboard Side. “A Third White, at the Weſt Point of the Bank Brack, which they are to leave on the Larboard Side. “And a Fourth, Black, at the Point of the Plateau of Mardyck; that is to ſay, at the moſt advanced Point of the Strand, oppoſite the Channel of Mardyck, which they are to leave on the Starboard ** Side. “. Navigators will therefore obſerve that the Three Black Buoy, “ above-mentioned are on the Land-Side, and the White One in the * Offing. “It has been reſolved by the Officers of the Admiralty eſtabliſhed for Flanders at Dunkirk aforeſaid, with the advice of the Deputies of the Pilotage, to order. Two more Buoys, to be laid at the Eaſt “Channel, to point out its Entrance.

- 1807 British Channel Pilot page 69 – Liverpool cones to starboard casks to port.

- 1816 Nautical survey of Firth of Tay Date: 1816. Scotland, red cans to port, B/W chequer cans to starboard, numbered.

- 1817 – 1852 Middle Ground buoys in Britain – not in the 1817 Nories. B&W and R&W striped buoys on the Gunfleet in 1852 but not middle grounds.

- 1823 Nories North Sea Pilot Dunkirk has numbered B, W & R buoys.

- 1839 British Channel Pilot – p118 Liverpool – The Buoys in the channels are so arranged , that on entering , those painted red are to be left on the starboard side , and those painted black on the larboard . Buoys striped black and white , are laid upon intervening banks or flats . Superior can- buoys with perches are placed at the elbows or turning points of the principal chan- nels . Each buoy bears the initial of the channel it occupies ; thus , F , signifies Formby Channel ; C , Crosby Channel ; H. F , Half tide Swashway ; N , New Chan- nel ; H , Horse Channel ; R , Rock Channel ; H. E. , Helbre Swash ; B , Beggar’s Patch ; L. Hoyle Lake ; & c . The buoys are likewise numbered in rotation , No. 1 denoting the outer or seaward buoy of its channel the letter indicates , Also – shows Culver sand to have RW stripe at west and Red to east. So Middle grounds appeared between 1840 and 1868.

- Liverpool in 1859, The Port and Town of Liverpool, and the Harbour, Docks, and Commerce of the Mersey

- 1868 Bristol Channel Chart shows Culver Sand with RWHS middle grounds, TH domain.

- West Coast Pilot 1870 Describes how to enter Liverpool from seaward: Thus, when inward bound, can buoys are to be left on the starboard hand, and nun, or conical buoys, on the port; the can buoys are painted red, and nun buoys black;

- 1874 Sailing Directions for the English Channel: The south coast of England, and general directions for the navigation of the Channel. The north coast of France, Parts 1-2 pp236 – BEACONS AND BUOYS . The following is the system of Buoys and Beacons on the coast of France : – When entering a channel from sea all buoys and beacons painted red with white band near the summit must be left to starboard , and those painted black to port . That part of the beacon which is below the level of high water , and all warping buoys are coloured white . The small rocky heads in frequented channels are coloured in the same way as the beacons , when they have a surface sufficiently conspicuous . Each beacon or buoy has upon it in full length or in abbreviation , the name of the danger it is meant to distinguish , likewise its number , commencing from sea- ward , and thus showing its numerical order in the same channel . The even numbers are on the red buoys , and the odd numbers on the black buoys ; the buoys and beacons coloured red , with black horizontal bands are named , not numbered .

- 1884 Sailing Directions for the West Coast of England– Liverpool red cans to starboard and black nuns to port.

- 1884 MERCHANT SHIPPING—UNIFORM SYSTEM OF BUOYAGE. Question in Parliament.

- 1884 Our seamarks; a plain account of the lighthouses, lightships, beacons, buoys, and fog-signals maintained on our coasts for the guidance of mariners mainly about fixed lights but describes the ‘Uniform System of Buouyage’. Notes there are about 1000 buoys and also has some drawings.

- 1886 Channel Pilot – see page 216 for the Uniform System of Buoyage

- 1889 Beacon Lights and Fog Signals Nature Article – describes the state of the art in lighting. Around 150 lit buoys worldwide.

- 1889 Beacon Lights and fog signals by Douglass, James N. (James Nicholas) 1826-1898 – lighthouse and buoy lighting.

- 1891 Sailing Directions for the West Coast of England – BUOYAGE . – The uniform system is adopted in buoying the several channels to the Mersey , and is such that , coming upon a buoy in the night the seaman may know by its shape on which side of the channel it is situated . An uniform system with respect to colour is likewise maintained as far as circumstances will allow . Thus , when inward bound , conical buoys are to be left on the starboard hand , can buoys on the port hand , and spherical buoys on either hand ; the conical buoys are painted red , can buoys black , and spherical buoys with horizontal stripes . On the buoys of every channel are painted the initial letter of the channel , with a number , the numerals being arranged in consecutive order , reckoning from seaward ; thus a conical buoy , marked Q. 1 , or a can buoy Q. 1 , denotes , respectively , the outer buoy on either side of Queen’s channel , the next buoys inward being marked Q. 2 , and so on for other channels . Fairway buoys bear the initial letter of their channel , and ” Fy . , ” and have distinct characteristics of form and colour .

- 1915 US Navy Scandinavia Pilot – covers Sweden, Denmark, Germany

- 1928 North coast of France pilot, including the Channel islands

- French uniform system of buoyage. — The following system of

- buoyage is established on the French coast. It comprises all marks, fixed or floating, which serve to indicate, by day, either existing dangers or the limits of navigable channels, namely, buoys, beacons, beacon towers or turrets, jetty heads, rocks, and convenient natural objects. It does not include ordinary landmarks and mooring buoys; mooring and warping buoys are painted white.

- The term ” starboard ” means the right-hand side approaching from seaward ; the term ” port ” means the left-hand side. The term ” separation marks ” is given to the marks placed at the seaward extremity of middle grounds, and the term ” junction marks ” is given to the marks placed at the inshore extremities of middle grounds. Marks placed on shoals of small extent are named ” isolated danger marks.”

- Starboard-hand marks are painted red and surmounted by a top mark of conical shape; if necessary, they are numbered with even numbers, commencing from seaward.

- Port-hand marks are painted black and surmounted by a top mark of cylindrical shape; if necessary, they are numbered with uneven numbers, commencing from seaward.

- Separation marks are painted white and black in horizontal stripes and surmounted by a top mark formed of 2 cones, bases together.

- Junction marks, are painted white and red, in horizontal stripes, and surmounted by a top mark formed of 2 cones, points together.

- Isolated danger marks are painted red and black, in horizontal stripes, and surmounted by a spherical top mark.

- Wreck marks, whether buoys or vessels, are painted green and surmounted by a top mark of the shape mentioned in the preceding articles 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, according to the case, and lights are used according to circumstances.

- N&jnes or numbers on marks are painted white.

- Stuart Mountfield. Western Gateway : A History of the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board, 1965.

- SOME HISTORY OF THE COASTWISE LIGHTS OF LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE

- Sailing Directions from Point Lynas to Liverpool

North America

- 1846 Report of the Secretary of the Treasury, on improvements in the light-house system and collateral aids to navigation. August 5, 1846. A US report on systems of buoyage and a thorough review of lighthouses in the UK and Europe.

- THE UNITED STATES LIGHTHOUSE SERVICE EDITION OF 1923

- CHRONOLOGY OF AIDS TO NAVIGATION AND THE UNITED STATES LIGHTHOUSE SERVICE 1716-1939

- FREQUENTLY CLOSE TO THE POINT OF PERIL:A HISTORY OF BUOYS AND TENDERS IN U.S. COASTAL WATERS 1789 – 1939 ©

- 1928 US Types of Buoys

- 1948 Buoys in the Waters of the U.S.

- COLOR OF LIGHTS

- For all buoys having lights, the following system of coloring is

- used. Green lights are used only on buoys marking the left-hand sides

- of channels entering from seaward. Red lights are used only on buoys

- marking the right hand sides of channels entering from seaward.

- White lights may be used on either side of the channel, and such lights

- are frequently employed in place of colored lights at points where a

- light of considerable brilliance is required, particularly as leading or

- turning lights.

- REFLECTORS

- Reflectors are placed upon many unlighted buoys, and greatly facili¬

- tate the locating of the buoys at night by means of a searchlight. Re¬

- flectors may be white, red, or green, and have the same significance as

- lights of these colors.

- LIGHT CHARACTERISTICS

- Fixed lights (lights that do not flash) may be found on either black

- or red buoys.

- Flashing lights (flashing at regular intervals and at the rate of not

- more than 30 flashes per minute) are placed on either black buoys or

- on red buoys.

- Quick flashing lights (not less than 60 flashes per minute) are placed

- on black buoys and on red buoys at points where it is desired to indi¬

- cate that special caution is required, as at sharp turns or sudden con¬

- strictions or where used to mark obstructions which may be passed only

- on one side.

- 1995 The Canadian aids to navigation system

Conferences & Reports

- 1848 London Gazette – Admiralty – STEAMERS’ LIGHTS.—To PREVENT COLLISION

- 1861 Vol 1 Report of Her Britanic Majesty’s Commissioners, appointed to inquire into the Condition and Management of Lights, Buoys, and Beacons, Submitted March 5, 1861, and presented to both Houses of Parliament by command of her Majesty. A great deal of information here including lightships and lighthouses.

- 1861 Vol 2 Lighthouse management : the report of the Royal Commissioners on Lights, Buoys Volume 2 – partially included in above but see at the end for Captain Beresford’s system

- 1861 from report – Liverpool – Buoys are distinguished by colour, red, black, or chequered red and black with white; or by form, nun, can, or pillar; or by sound bell. By the initial letters of their channel painted on them with a number. Those situated at elbows or turning points are distinguished by a perch and ball. Two bell beacons are now in position, and all others are distinguished by one or more of the characteristics named.

- 1861 from the report – Liverpool – On the 15th of July, 7 captains of Mr. MacIver’s steamers, were examined. They all considered the buoys in Queen’s Channel very good, and that the principle, viz., SHAPE and COLOCR different on different sides should be made universal. (In Dublin and in Liverpool the systems differ. Under the Trinity House there is no system. In Scotland, there is colour only. In Hull the colour is reversed.)

- 1883 Nautical Magazine VOLUME LII.-No. VIII. AUGUST , 1883 . see page 573 for the UNIFORM SYSTEM OF BUOYAGE

- 1889 International Marine Conference (1889 : Washington D.C.) pp264-267 for buoyage.

- 1890 Protocols of Proceedings of the International Marine Conference Volume 3 also International marine conference

- 1914 Manual of navigation, 1914 by Great Britain. Admiralty pp220 for buoyage.

- 1924 The International Hydrographic Bureau By Lieutenant Commander George E. Brandt, U. S. Navy background history.

- 1936 League of Nations Uniform System of Buoyage Document and Drawings.

- Nares, J. D., and H. Bencker. ‘Uniformity in Buoyage’. The International Hydrographic Review, 1945. A thorough account of what had happened by 1946 including all the minor conferences.

- 1978 THE BACKGROUND TO IALA BUOYAGE SYSTEM “ A ” by Captain J. E. BURY – the man who drove through the IALA System, was very informative.

- Clearman, Brian. ‘INTERNATIONAL MARINE AIDS TO NAVIGATION’, 2010 – – a good historical account. of the various attempts to find a common system.

- 2050 Maritime 2050 Navigating to the Future.

- 1985 Naish, John Michael. Seamarks : Their History and Development. London : Stanford Maritime, 1985. The most thorough account found of Seamarks including buoys.

- IALA AISM. ‘A History of Floating Aids to Navigation by Adrian H Wilkins’ is well illustrated and informative on technology, especially lighting.

- Trinity House Buoys present-day practice and description of IALA.

- Explanation of the IALA system.

- The American Practical Navigator/Chapter 5

- R1001 THE IALA MARITIME BUOYAGE SYSTEM

Miscellaneous

- https://trinityhousehistory.wordpress.com/

- U.S. Naval Institute. ‘The Atomic Buoy Experiment’,

- The International Association of Lighthouse Authorities – Varne Disaster.

- Pathe Films on buoys.

- Science Museum Collection of Buoys

- Wikipedia Thames Estuary

- Timeline List

- 1970 System of buoyage and beaconage for New Zealand.

Lighting, Lighthouses and Lightships

- 1889 Nature Beacon Lights and Fog Signals

- Automatic Power Company History

- THE ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA A DICTIONARY OF ARTS, SCIENCES, LITERATURE AND GENERAL INFORMATION ELEVENTH EDITION – very good on Lighthouse/Lightships and lighting.

- A Brief History of Ship Navigation Lights – what it says plus a shop for ship lights.

- Lightships and Lighthouses – separate section.

- https://www.angeln1.de/alles-ueber-feuerschiffe-die-schwimmenden-leuchttuerme/ – German Lightships

H.M.Denham

- Henry Mangles Denham

- On the survey of the Mersey and the Dee

- https://www.icevirtuallibrary.com/doi/pdf/10.1680/imotp.1888.21004

- https://www.pdavis.nl/ShowBiog.php?id=449

- https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp120670/sir-henry-mangles-denham

Captain J.E.Bury

Captain John Bury, Elder Brother of Trinity House and Master Mariner, was born on July 28, 1915. He died on October 17, 2006, aged 91

Captain John Bury Times Obit.

John Bury (captain) – Wikipedia

Examples of buoy colours 1930-1950

- Buoys of Cowes harbour says Red Cans to port in 1936

- The Belfast Buoys – example of pre-IALA

- 1935 USNO HO114 Sailing directions for the east coast of England from Fife Ness to North Foreland including the Firth of Forth and the Thames Black cans to port and red cones to starboard – USB

- 1942 USNO HO114 says cans to port, cones to starboard, solid colours.

- 1944 USNO HO114 Supplement has some red cans and some red cones

- 1952 USNO HO31 says port Red can with T, Starboard Black Cone – consistent with 1950 change.

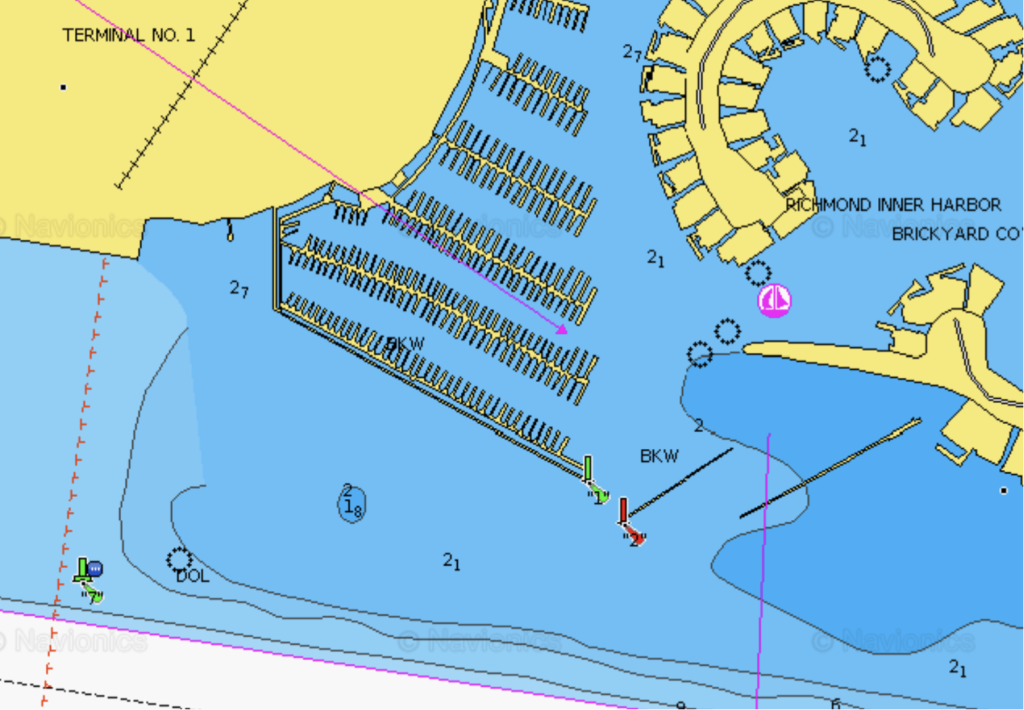

- A U.S. Marina showing green fixed to starboard.

Footnotes

- 1For chains, see ‘Caesar • Gallic War—Book III’. For Cooperage

- 2

- 3Hanseatic League and King’s Lynn

- 4

- 5IALA AISM. ‘A History of Floating Aids to Navigation by Adrian H Wilkins’.

- 6Ballast Board became Irish Lights

- 7See the 1844 Coasters Guide where buoys are learned by rote.The 1847 Sailing directions for the river Thames, from London enable the navigator to plan a route buoy to buoy.

- 8The New British Channel Pilot. Containing Sailing Directions from London and Yarmouth to Liverpool, and from Ostend to Brest. Also for the Coast of Ireland, from Dublin to Galway Bay … The Whole Connected, Arranged and Improved by William Heather. 4th Ed

- 9

- 101839 British Channel Pilot – p118 Liverpool – The Buoys in the channels are so arranged, that on entering, those painted red are to be left on the starboard side, and those painted black on the larboard. Buoys striped black and white, are laid upon intervening banks or flats. Superior can- buoys with perches are placed at the elbows or turning points of the principal channels. Each buoy bears the initial of the channel it occupies; thus , F , signifies Formby Channel; C , Crosby Channel ; H. F , Half tide Swashway ; N , New Channel; H , Horse Channel ; R , Rock Channel ; H. E. , Helbre Swash; B , Beggar’s Patch ; L. Hoyle Lake ; & c . The buoys are likewise numbered in rotation , No. 1 denoting the outer or seaward buoy of its channel the letter indicates.

- 11The French system from 1839 was red cans to starboard and black cones to port with naming and numbering, there were various striped buoys and topmarks. It is unclear when this started.

- 12The US in any case mostly used spar or cask buoys.

- 13Colregs see Bahr, Rudiger. ‘The Development of Regulations for Preventing Collisions in Inland, Inshore, and Open Waters of the UK during the First Half of the Nineteenth Century’. Thesis, University of St Andrews, 1998. https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/handle/10023/14084.

- 14Liiverpool in the 1815 survey by George Thomas has cask buoys at key points

- 15Liverpool Buoyage see page 130 Admiralty hydrography dept, Sailing Directions for the West Coast of England, West Coast of England Pilot. Admiralty Notices to Mariners, 1870.

- 16Hull- see 1861 Report of Her Britanic Majesty’s Commissioners, appointed to inquire into the Condition and Management of Lights, Buoys, and Beacons, Submitted March 5, 1861 page 319 – XXVII. All the buoys on the south side of the Humber are coloured red, with a horizontal white stripe, and numbered 1 to 12, commencing with the sand hale buoy, and terminating with the westernmost buoy on the upper middle, opposite the town of Hull. The buoys on the north side are all black, and numbered 1 to 12, commencing with the outer binks buoy, and terminating with the upper hebbles buoy. The buoys on the middle sands or shoals in the lower part of the Humber are all chequered black and white. The hook buoy on the lower middle is painted white, and marked “book middle.” had the opposite, and so on.

- 171874 Sailing Directions for the English Channel: The south coast of England, and general directions for the navigation of the Channel. The north coast of France, Parts 1-2 pp236 – BEACONS AND BUOYS . The following is the system of Buoys and Beacons on the coast of France : – When entering a channel from sea all buoys and beacons painted red with white band near the summit must be left to starboard , and those painted black to port . That part of the beacon which is below the level of high water , and all warping buoys are coloured white . The small rocky heads in frequented channels are coloured in the same way as the beacons , when they have a surface sufficiently conspicuous . Each beacon or buoy has upon it in full length or in abbreviation , the name of the danger it is meant to distinguish , likewise its number , commencing from sea- ward , and thus showing its numerical order in the same channel . The even numbers are on the red buoys , and the odd numbers on the black buoys ; the buoys and beacons coloured red , with black horizontal bands are named , not numbered .

- 181891 Sailing Directions for the West Coast of England – BUOYAGE . – The uniform system is adopted in buoying the several channels to the Mersey , and is such that , coming upon a buoy in the night the seaman may know by its shape on which side of the channel it is situated . An uniform system with respect to colour is likewise maintained as far as circumstances will allow . Thus , when inward bound , conical buoys are to be left on the starboard hand , can buoys on the port hand , and spherical buoys on either hand ; the conical buoys are painted red , can buoys black , and spherical buoys with horizontal stripes . On the buoys of every channel are painted the initial letter of the channel , with a number , the numerals being arranged in consecutive order , reckoning from seaward ; thus a conical buoy , marked Q. 1 , or a can buoy Q. 1 , denotes , respectively , the outer buoy on either side of Queen’s channel , the next buoys inward being marked Q. 2 , and so on for other channels . Fairway buoys bear the initial letter of their channel , and ” Fy . , ” and have distinct characteristics of form and colour .

- 19See Charles Babbage and Lighting, not implemented but interesting.

- 20Pintsch gas lighting system

- 211883 Nautical Magazine VOLUME LII.-No. VIII. AUGUST , 1883 . see page 573 for the UNIFORM SYSTEM OF BUOYAGE.

- 22See A Description & Plat of the Sea-Coasts of England, 1653

- 23See the 1839 Pilot and 1868 Bristol Channel Chart. Middle grounds were in Bedford’s proposal, were used in Liverpool,

- 241852 A new chart of the River Thames inc. Harwich and 1907 Reynold’s new chart of the Thames Estuary see Oaze & Girdler.

- 25See United States Hydrographic Office, British Islands Pilot: East Coasts of Scotland and England (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1915) page 34 – Coloring of buoys . – In carrying out the above uniform system on the east coast of England the colors adopted by the Trinity Houses of London and Newcastle are whole colors on the starboard hand and parti – colors on the port hand ; in Scotland starboard hand buoys are painted red and port hand buoys black

- 261936 Geneva Cardinals – ‘The cardinal system is generally used to indicate dangers where the coast is flanked by numerous islands, rocks and shoals, as well as to indicate dangers in the open sea. In this system, the bearing (true) of the mark from the danger is indicated to the nearest cardinal point.’

- 27See Deben Beacons

- 1For chains, see ‘Caesar • Gallic War—Book III’. For Cooperage

- 2

- 3Hanseatic League and King’s Lynn

- 4

- 5IALA AISM. ‘A History of Floating Aids to Navigation by Adrian H Wilkins’.

- 6Ballast Board became Irish Lights

- 7See the 1844 Coasters Guide where buoys are learned by rote.The 1847 Sailing directions for the river Thames, from London enable the navigator to plan a route buoy to buoy.

- 8The New British Channel Pilot. Containing Sailing Directions from London and Yarmouth to Liverpool, and from Ostend to Brest. Also for the Coast of Ireland, from Dublin to Galway Bay … The Whole Connected, Arranged and Improved by William Heather. 4th Ed

- 9

- 101839 British Channel Pilot – p118 Liverpool – The Buoys in the channels are so arranged, that on entering, those painted red are to be left on the starboard side, and those painted black on the larboard. Buoys striped black and white, are laid upon intervening banks or flats. Superior can- buoys with perches are placed at the elbows or turning points of the principal channels. Each buoy bears the initial of the channel it occupies; thus , F , signifies Formby Channel; C , Crosby Channel ; H. F , Half tide Swashway ; N , New Channel; H , Horse Channel ; R , Rock Channel ; H. E. , Helbre Swash; B , Beggar’s Patch ; L. Hoyle Lake ; & c . The buoys are likewise numbered in rotation , No. 1 denoting the outer or seaward buoy of its channel the letter indicates.

- 11The French system from 1839 was red cans to starboard and black cones to port with naming and numbering, there were various striped buoys and topmarks. It is unclear when this started.

- 12The US in any case mostly used spar or cask buoys.

- 13Colregs see Bahr, Rudiger. ‘The Development of Regulations for Preventing Collisions in Inland, Inshore, and Open Waters of the UK during the First Half of the Nineteenth Century’. Thesis, University of St Andrews, 1998. https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/handle/10023/14084.

- 14Liiverpool in the 1815 survey by George Thomas has cask buoys at key points

- 15Liverpool Buoyage see page 130 Admiralty hydrography dept, Sailing Directions for the West Coast of England, West Coast of England Pilot. Admiralty Notices to Mariners, 1870.

- 16Hull- see 1861 Report of Her Britanic Majesty’s Commissioners, appointed to inquire into the Condition and Management of Lights, Buoys, and Beacons, Submitted March 5, 1861 page 319 – XXVII. All the buoys on the south side of the Humber are coloured red, with a horizontal white stripe, and numbered 1 to 12, commencing with the sand hale buoy, and terminating with the westernmost buoy on the upper middle, opposite the town of Hull. The buoys on the north side are all black, and numbered 1 to 12, commencing with the outer binks buoy, and terminating with the upper hebbles buoy. The buoys on the middle sands or shoals in the lower part of the Humber are all chequered black and white. The hook buoy on the lower middle is painted white, and marked “book middle.” had the opposite, and so on.

- 171874 Sailing Directions for the English Channel: The south coast of England, and general directions for the navigation of the Channel. The north coast of France, Parts 1-2 pp236 – BEACONS AND BUOYS . The following is the system of Buoys and Beacons on the coast of France : – When entering a channel from sea all buoys and beacons painted red with white band near the summit must be left to starboard , and those painted black to port . That part of the beacon which is below the level of high water , and all warping buoys are coloured white . The small rocky heads in frequented channels are coloured in the same way as the beacons , when they have a surface sufficiently conspicuous . Each beacon or buoy has upon it in full length or in abbreviation , the name of the danger it is meant to distinguish , likewise its number , commencing from sea- ward , and thus showing its numerical order in the same channel . The even numbers are on the red buoys , and the odd numbers on the black buoys ; the buoys and beacons coloured red , with black horizontal bands are named , not numbered .

- 181891 Sailing Directions for the West Coast of England – BUOYAGE . – The uniform system is adopted in buoying the several channels to the Mersey , and is such that , coming upon a buoy in the night the seaman may know by its shape on which side of the channel it is situated . An uniform system with respect to colour is likewise maintained as far as circumstances will allow . Thus , when inward bound , conical buoys are to be left on the starboard hand , can buoys on the port hand , and spherical buoys on either hand ; the conical buoys are painted red , can buoys black , and spherical buoys with horizontal stripes . On the buoys of every channel are painted the initial letter of the channel , with a number , the numerals being arranged in consecutive order , reckoning from seaward ; thus a conical buoy , marked Q. 1 , or a can buoy Q. 1 , denotes , respectively , the outer buoy on either side of Queen’s channel , the next buoys inward being marked Q. 2 , and so on for other channels . Fairway buoys bear the initial letter of their channel , and ” Fy . , ” and have distinct characteristics of form and colour .

- 19See Charles Babbage and Lighting, not implemented but interesting.

- 20Pintsch gas lighting system

- 211883 Nautical Magazine VOLUME LII.-No. VIII. AUGUST , 1883 . see page 573 for the UNIFORM SYSTEM OF BUOYAGE.

- 22See A Description & Plat of the Sea-Coasts of England, 1653

- 23See the 1839 Pilot and 1868 Bristol Channel Chart. Middle grounds were in Bedford’s proposal, were used in Liverpool,

- 241852 A new chart of the River Thames inc. Harwich and 1907 Reynold’s new chart of the Thames Estuary see Oaze & Girdler.

- 25See United States Hydrographic Office, British Islands Pilot: East Coasts of Scotland and England (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1915) page 34 – Coloring of buoys . – In carrying out the above uniform system on the east coast of England the colors adopted by the Trinity Houses of London and Newcastle are whole colors on the starboard hand and parti – colors on the port hand ; in Scotland starboard hand buoys are painted red and port hand buoys black

- 261936 Geneva Cardinals – ‘The cardinal system is generally used to indicate dangers where the coast is flanked by numerous islands, rocks and shoals, as well as to indicate dangers in the open sea. In this system, the bearing (true) of the mark from the danger is indicated to the nearest cardinal point.’

- 27See Deben Beacons