Roughs Tower, marked by its northwest and southeast cardinals, has stood sentinel seven miles offshore from Harwich and Felixstowe since 11th February 1942. The fort’s past is much more interesting than one might think.

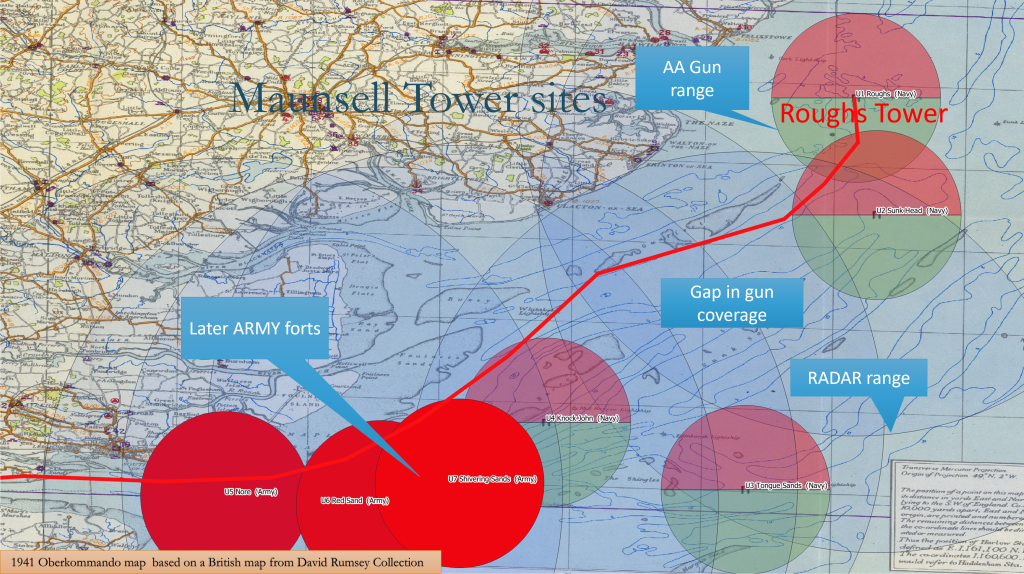

The sister Knock John Tower and metal Army forts are further south in the Estuary near the Kent shore. The Army’s War of the Worlds’ forts look fascinating, but Roughs was the first and has the best story.

Maunsell Towers

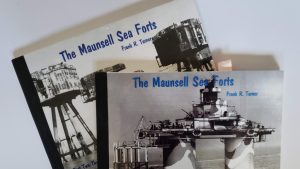

All are known as Maunsell Towers, four were Navy, and three were Army: all are from World War Two. You might assume that the Navy could not agree on a common design with the Army, but this was not so, and Guy Maunsell designed both types. Not all have survived.

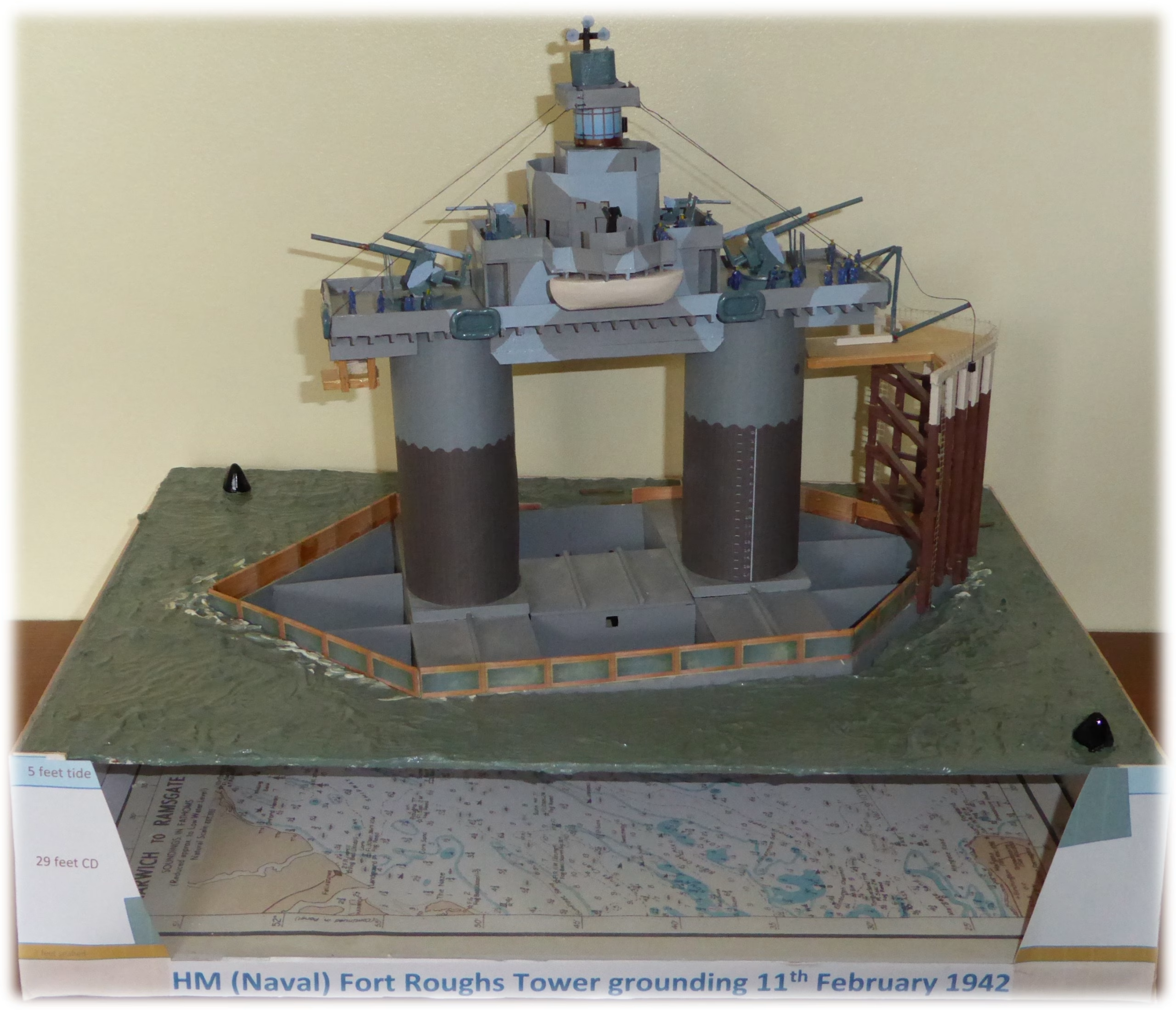

A Rough Model

To help understand the grounding process and, for a 2020 COVID lockdown project, I made a 1:144 scale model of Roughs Tower from scratch using the scraps to hand. The tower had something to do with air defence and was a self-declared Principality but that was all I knew.

Research

So, research was needed, and what follows is what came to light. The frightening journey of the structure from where it was built to the site was a revelation.

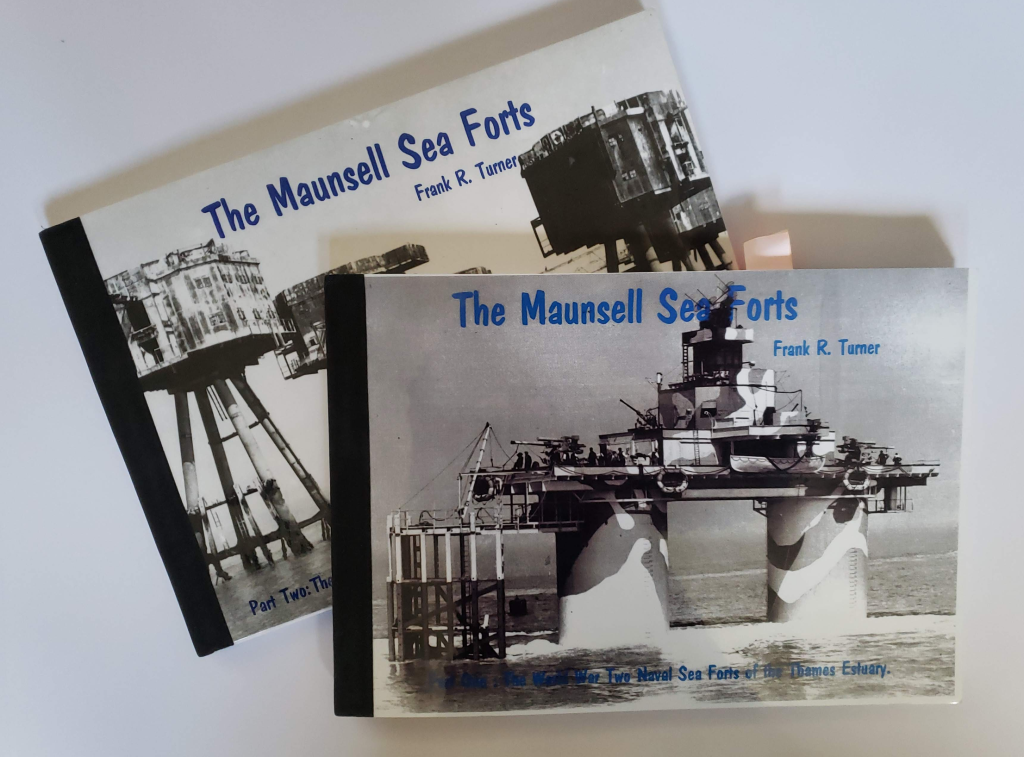

It helps first to know why it was there, how it worked and the overall fort system. John Posford, Maunsell’s assistant and later partner, wrote an account of the fort’s construction and deployment in 1948. This provided some of the information for the definitive books by Frank Turner which were a primary source. Other sources include the Maunsell Sea Forts Appreciation group, the Fort Fanatics website and others, such as the 28 Days Later explorers group who used a crossbow-fired grapnel to get onto Rough’s sister, Knock John, in 2018 and took great photos.

Mines

In 1940 Adolf Hitler had overrun Europe and was keen to include our Sceptred Isle in his scheme. Britain had endured the Blitz but was still taking a battering from enemy aircraft which could cross the sea in less than half an hour. Planes and boats were dropping mines in the Thames Estuary to sink British East Coast convoys. It would take until 1948 to finally clear them. One consequence of the air-dropped magnetic mines was a tragic collection of green wreck buoys on late 1940s charts. This summary from the Southend Timeline website gives an idea of the situation. Bombs or mines were being dropped daily.

- Sunday 21st July 1940: Mines laid in Thames Estuary.

- Monday 22nd July 1940: Shipping bombed in Estuary.

- Tuesday 23rd July 1940: Mines laid in Thames Estuary.

- Thursday 25th July 1940: Mines laid in Thames Estuary.

- Friday 26th July 1940: Estuary bombed.

- Sunday 28th July 1940: Mines laid in Thames Estuary.

- Monday 29th July 1940: Mines laid in Thames Estuary.

- Wednesday 31st July 1940: Mines laid in Thames Estuary; Southend bombed; RAF Rochford bombed.

- Thursday 1st August 1940: Mines laid in Thames Estuary.

- Friday 2nd August 1940: Mines laid in Thames Estuary.

- Tuesday 6th August 1940: Mines laid in Thames Estuary.

- Wednesday 7th August 1940: Mines laid in Thames Estuary; localized raids on Southend area.

- Thursday 8th August 1940: Mines laid in Thames Estuary.

- Friday 9th August 1940: Mines laid in Thames Estuary.

Anti-aircraft defence out to sea was needed. Guy Maunsell was a Civil Engineer who honed his skills building fixed and floating docks as well as concrete ships in the Great War. An early assignment was building eight massive towers, connected by nets, spanning the Channel to foil enemy submarines.

Maunsell’s Ideas

Early in World War Two, Maunsell proposed a chain of submersible observation posts along the coast of Europe. These 160-ton concrete vessels, with a crew of five working in two-week shifts, would report by radio. They would submerge if attacked and surface some hours later. RADAR made these unnecessary. He next proposed a chain of concrete pontoon-based gun forts to blockade the enemy.

Little attention was paid to these ideas until the requirement for Thames Estuary Special Defence Units late in 1940. Maunsell made several proposals and was awarded the project.

Work Commences

Work commenced in June 1941 at Red Lion Wharf Northfleet on the Thames; the first deployment planned for December. Maunsell used a ferroconcrete construction system: there are other structures in the Estuary built in the same way such as FCBs.

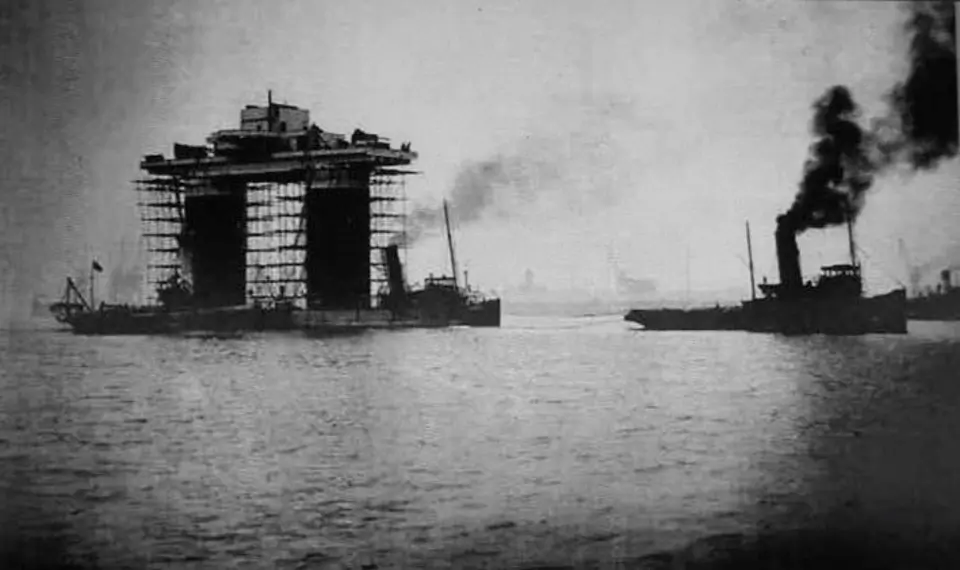

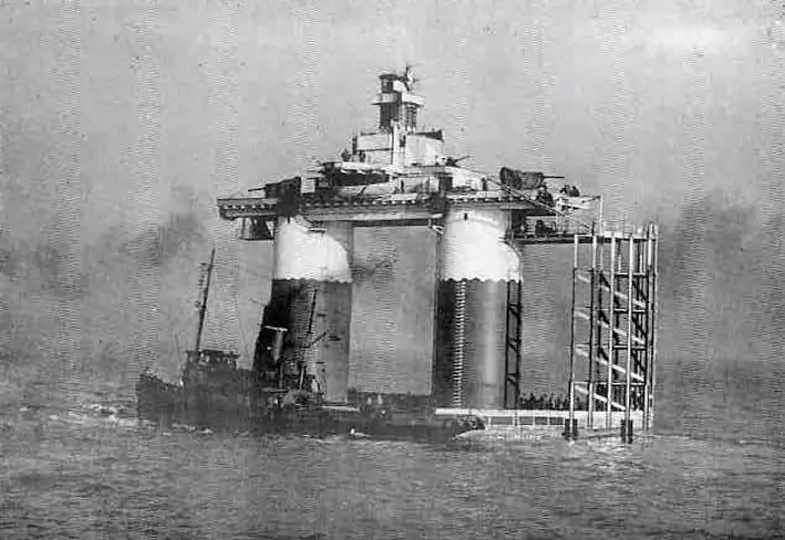

Northfleet was also where Nelson’s HMS Medusa was built 140 years earlier. The forts would be towed to the deployment sites fully manned and equipped for action immediately after they were positioned. Each Fort was a 2000-ton floating concrete pontoon supporting two 24 ft diameter, 66ft high concrete towers. After six months of construction, on New Year’s Day of 1942, the first fort was towed north by tug to Tilbury for fitting out and was inspected by the Navy on the 29th of January. The fort drew 11ft of water with a freeboard of only 3ft, so removable timber gunwales were added to reduce the amount of water shipped.

A week before this first fort sailed the Admiralty realised that re-supply from ship to deck would be difficult so a wooden “Dolphin” was designed and built at great speed. None of these have survived and must have taken a battering from supply vessels alongside.

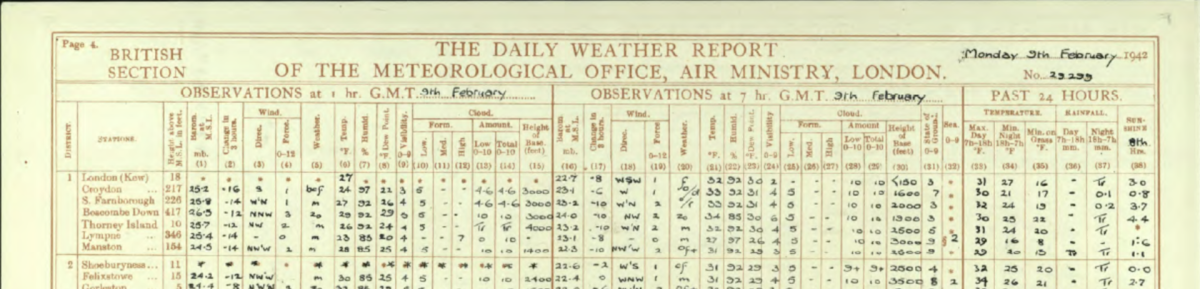

The Weather

Maunsell wanted fair weather and a north-westerly, which is odd since a south-westerly should be better. He originally planned to leave in time to pass the defence boom before nightfall.

On Sunday 8th Feb 1942, the first fort was named His Majesty’s Fort Roughs Tower and moved to be degaussed. This is a magnetic process to mitigate the threat from mines: as the fort was made of concrete, the reinforcement metal was the likely risk.

Embarkation

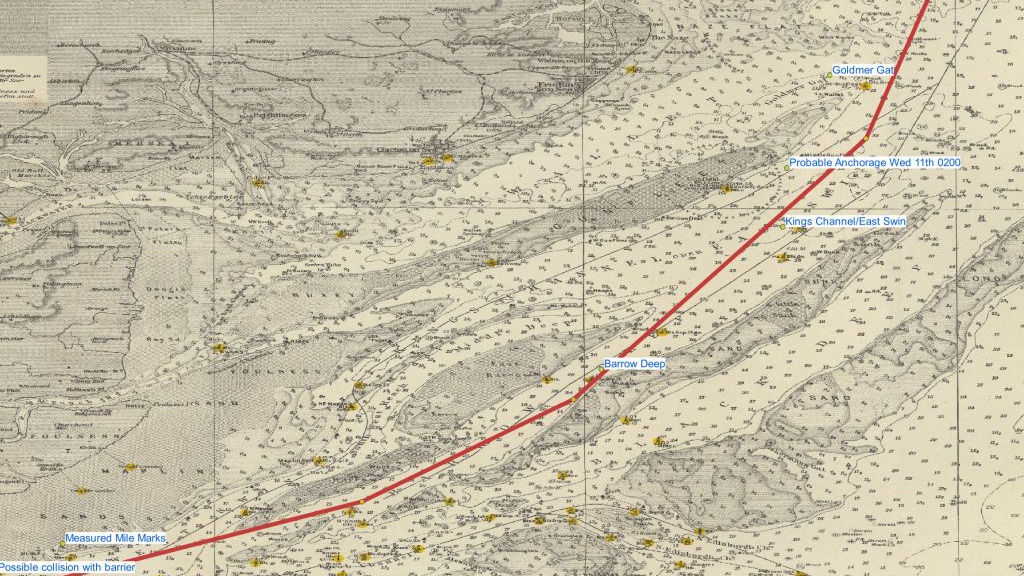

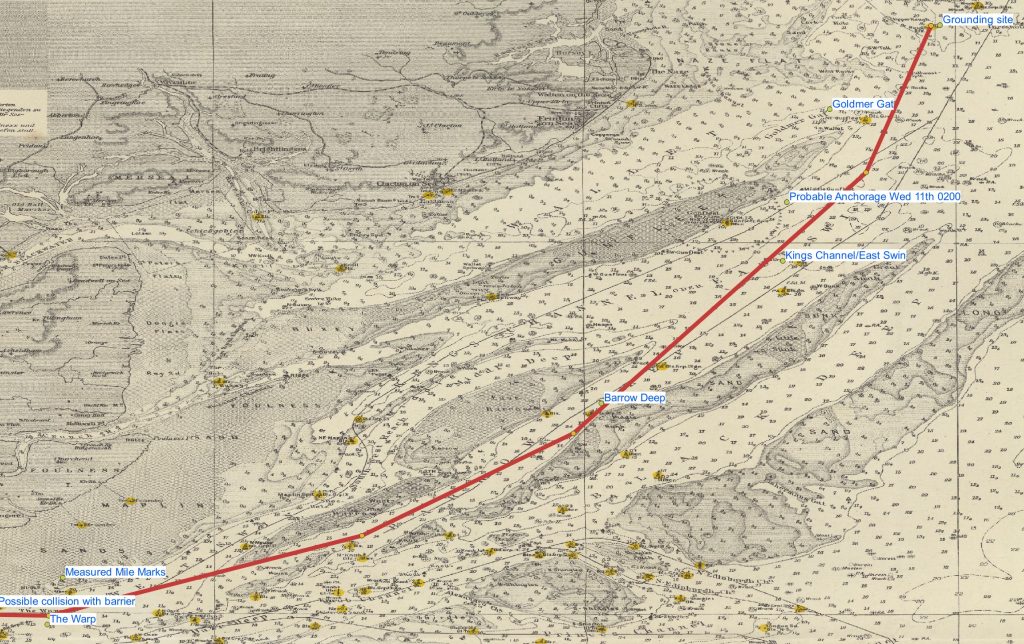

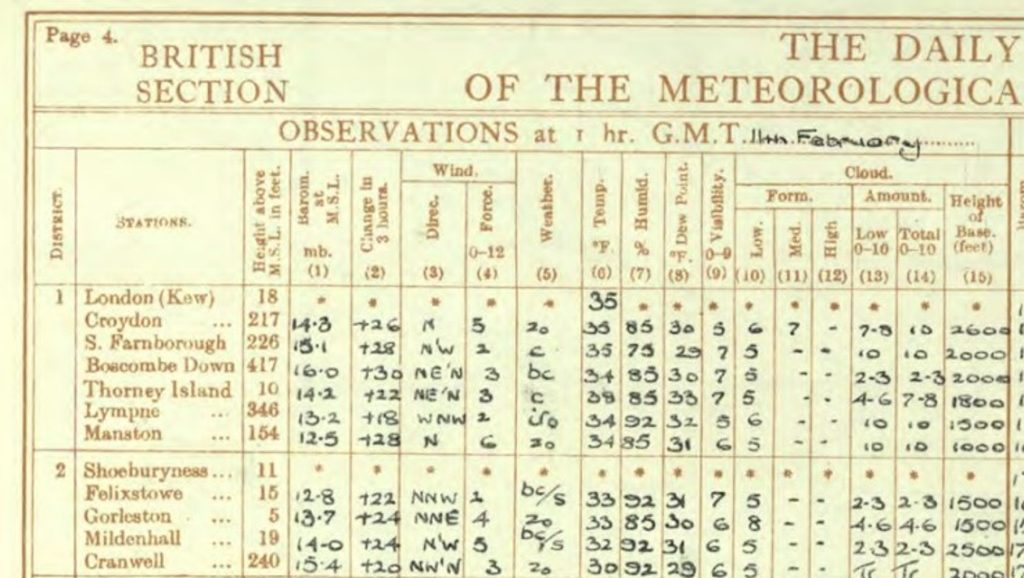

At this point, the crew of 100 or so would have embarked and on Monday morning the Fort and its four tugs1The tugs were Dapper, Lady Brassey, Crested Cock and King Lear departed at 0915 along Gravesend Reach. It was foggy and cold at 37F (2C) with a westerly light wind but a falling barometer2See Met Office Report . According to the account, the weather had caused delays in the days before, although the met reports are not that bad. From the Met Office report, Monday morning was OK apart from the fog. Although Saturday was bad Sunday looked reasonable so why didn’t they leave then?

Departure

Guy Maunsell and his new site engineer, John Posford were in the tugs.

Within thirty minutes the fort collided with a line of Lightships, moving several from their moorings and resulting in robust naval language, shortly afterwards a buoy was fouled. This was followed with thirty minutes, in the Lower Hope, by hitting two of the Mucking buoys. Due to the fog the fleet anchored at West Blyth, losing two hours of valuable ebb. For non-sailors, or those unfamiliar with the Estuary an ebb tide should be helpful for this voyage and a flood tide resists progress. However, with this tow, they discovered that the increased steerage way from towing against the flood gave them better control at the cost of lost speed.

They then took 2 1/2 hours to tow 5 nM along Sea Reach against the flood and anchored for the night by the old Chapman Lighthouse off Canvey. Fortunately, they did not hit it as they would have gone aground.

The Second Day

On Tuesday morning Maunsell and his team went ashore for two hours in Southend, this did not appear to involve the Navy or Posford. Maunsell returned in time to set off just below low water and tow the remaining 5 nM of Sea Reach against the flood. The Navy is in the habit of sailing with the “utmost dispatch” and would naturally have wanted to use the ebb from about 0600 to 1300 rather than setting off against the flood. Just as with the delay in sailing the following day, something seems amiss.

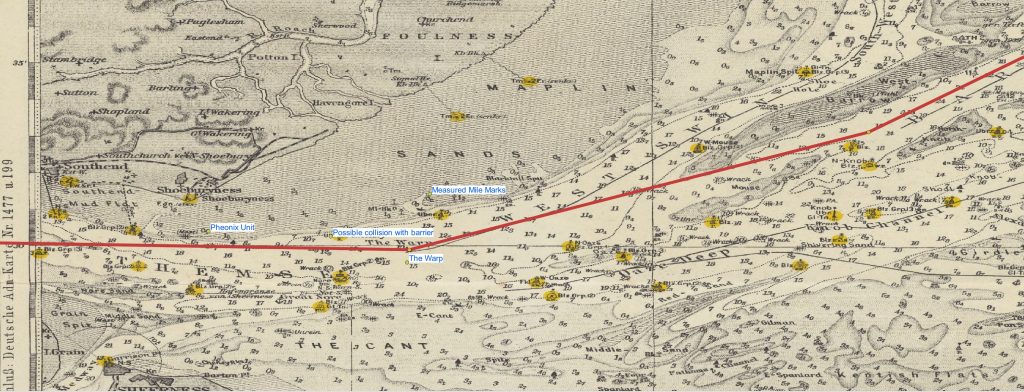

They passed near where a “Phoenix”3Another ferroconcrete structure unit would soon be abandoned on the Maplin Sand. These were part of the D-day Mulberry Harbour project. The original idea was Maunsell’s but he initially got no credit. He was later recognised by one of the plaques on the Mulberry B monument to the British Royal Engineers at Arromanches with an inscription:

Original Floating Harbour Concept- Mr Guy A. Maunsell

Roughs was the most northerly fort site, so they would also have passed close to future sites for the other towers. But why did they do the most difficult deployment first? The Navy forts U1 to U4 are to the east shown with their gun ranges split red and green. There is a gun coverage gap in the system, it could have been avoided by placing one of the forts differently.

On the fort, nobody could see anything as, by Southend, a blizzard had started, and the wind increased. This would have made navigation difficult. At 15:00 they passed through the gate in the seven-mile-long defensive boom that ran between the Sheerness and Shoeburyness and collided with4 collision with barrier see http://www.bobleroi.co.uk/ScrapBook/CityReunion/FortFanatics.html.5See the account of George Tapper in BATES, MICHAEL. PRINCIPALITY OF SEALAND: Holding the Fort. 2015.. If this happened this appears not to have been serious.

Beyond the barrier, the preceding minesweepers detonated a number of mines along the route6Mines – see the account of George Tapper.. The tow continued over Tuesday evening with a strong northwesterly and heavy swell, RAF Manston Kent recorded a northerly force six at 0100 on Wednesday and Gorleston force four so the wind at sea was probably a northerly five or six. Remember this was February, snowing and the middle of the night. They battled up the channel into the Warp. The Warp, West Swin, then Middle Deep was the shortest route. There are ample opportunities to go aground on the sands with an 11 ft draught which must have been a concern. For example, at Maplin, at the entrance to the Middle Deep, the channel is only half a mile wide between two drying sandbanks. The 5nM longer route up the Barrow Deep gives more sea room so it was probably preferred.

The fort had no rudder or keel and was like a 100-foot-high floating apartment block: it would have weathercocked along the axis of the North Westerly wind.

The Stormy Second Night

Navigation at night in the snow would have been further hampered by the lack of navigation aids. The lightships had been removed in 1941 following air attacks, locally, the East Oaze Lightship had been sunk in 19407East Oaze, sunk 1 November 1940. .The peacetime buoys had been replaced by a sparse chain of ‘B’ marks for the East Coast convoys. Maplin lighthouse had been decommissioned in 1921 and Gunfleet in 19398Lights and Lighthouses were only lit under War Office instructions. “The principal keeper would receive a war office telegram telling them to exhibit the light on a certain night or nights between the hours of such and such. Right up until 30yrs ago we still held on station the war coverings for the lens which only allowed the central bullseyes to be shown, thus reducing the magnification and therefore the distance the light could be seen. Offshore lights communication was by radio. UK Lighthouses | Facebook Bill Arnold.”.

They must have made satisfactory progress in the six hours of ebb into the King’s Channel, but all was not well as water had been shipped over the wooden gunwales and the pumps had failed due to wet terminals. Two of the four tugs broke their tow and so, at 0200 on Wednesday morning, they anchored.

It looks as if they reached somewhere near the head of the Gunfleet which would have given some shelter. The tug “Dapper” had a sufficiently strong anchor cable to hold itself and 4000 tons9The displacement of the Fort works out at 3300 tons, 126′ net length’x88′ beam ‘x11 ‘draught gives 3293 cubic metres x 1.03 tons per cubic metre. of the fort against the combined blizzard and flood. The period at anchor, in the dark and snow, was used to repair the damaged wooden gunwales, fix the pumps and pump out the water. They wanted the fort to sink, but not yet. John Posford’s account merely mentions an “anxious night”. Remember that the hundred-plus crew were on board the tower, at the top.

The Third Day

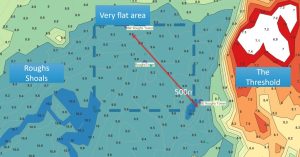

Conditions improved on Wednesday morning. There must have been a particularly good reason to waste nearly all the helpful ebb from 0900 to 1500. The accounts differ but it seems they weighed anchor at 1400 and covered the short distance to Roughs Shoals via Goldmer’s Gat by 1600: another strange delay.

Safely Aground at Last

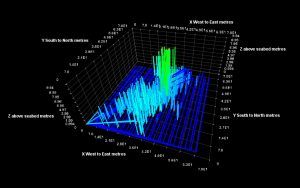

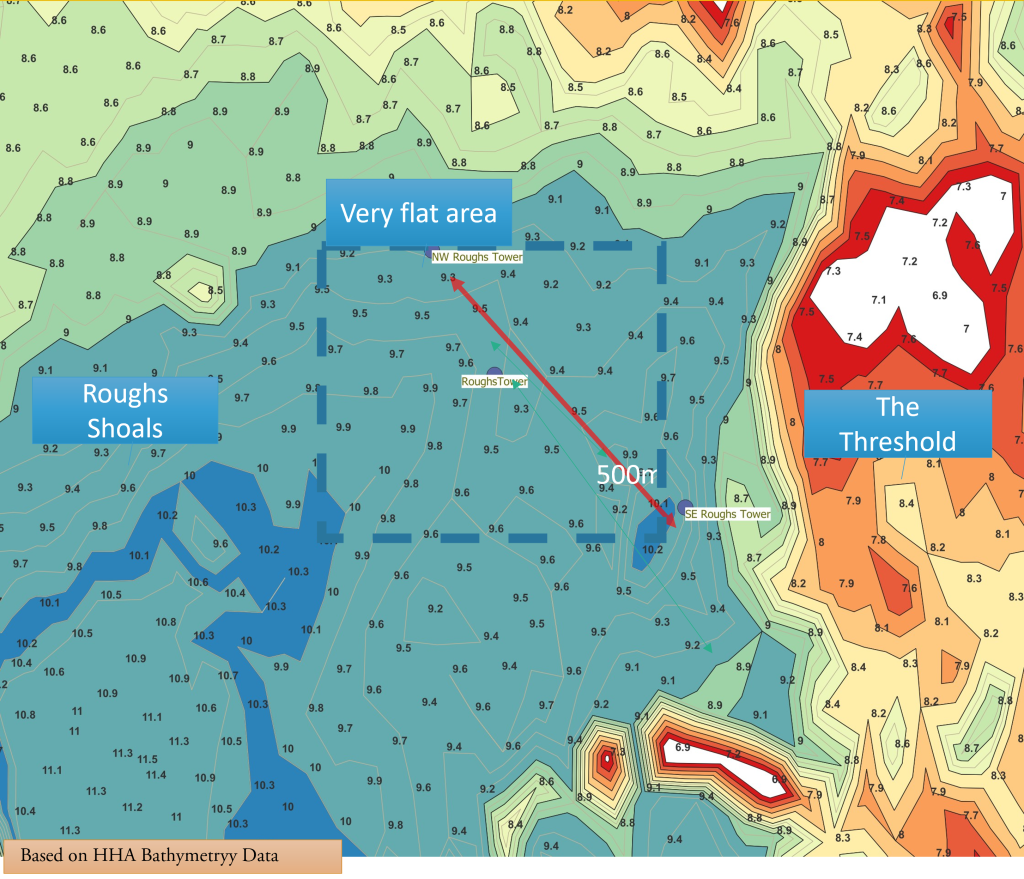

Roughs Tower was grounded near, but not on, Rough Shoals. In the selected area to east of the shoals, the seabed is sand and pebbles. On this diagram, the distance between the buoys is 500m and the contours are only 0.2 m showing the area around the fort in light blue. Unlike the Roughs Shoals to the west and Threshold to the east, the site is very smooth. The bottom is flat with a slope of much less than 1% shown by the spot depths on modern bathymetry. The area was a wise choice since it was a hazard to shipping and, indeed, a cluster of WWII wrecks lies on the adjacent Threshold.

Having arrived on site it is worth looking at the Interior and Operation of the Fort.

But next, the Fort had to be sunk, this was a dramatic event and continued in:

Next Section The Grounding of Roughs Tower:

Notes

Tugs

- Crested Cock – took boards

- King Lear – damaged in lightship collision, took boards

- Dapper – last to cast off

- Lady Brassey

Dapper

Originally Chapman built New York 1915 so different from the others.

https://www.doverferryphotosforums.co.uk/dhb-dapper-past-and-present/

https://historicalrfa.uk/rfa-dapper/

https://thamestugs.co.uk/THAMES-AT-WAR.php – from comments on this one she may not have been the best choice.

Built by New York Shipbuilding for Merritt-Chapman & Scott as Wm E Chapman, according to Dover Ferry Photographs. LR registered number 18887

Questions

Footnotes

- 1The tugs were Dapper, Lady Brassey, Crested Cock and King Lear

- 2

- 3Another ferroconcrete structure

- 4collision with barrier see http://www.bobleroi.co.uk/ScrapBook/CityReunion/FortFanatics.html.

- 5See the account of George Tapper in BATES, MICHAEL. PRINCIPALITY OF SEALAND: Holding the Fort. 2015.

- 6Mines – see the account of George Tapper.

- 7

- 8Lights and Lighthouses were only lit under War Office instructions. “The principal keeper would receive a war office telegram telling them to exhibit the light on a certain night or nights between the hours of such and such. Right up until 30yrs ago we still held on station the war coverings for the lens which only allowed the central bullseyes to be shown, thus reducing the magnification and therefore the distance the light could be seen. Offshore lights communication was by radio. UK Lighthouses | Facebook Bill Arnold.”

- 9The displacement of the Fort works out at 3300 tons, 126′ net length’x88′ beam ‘x11 ‘draught gives 3293 cubic metres x 1.03 tons per cubic metre.

Image Sources and Credits

Image Credits and Sources

- Tow-to-site: Photo from www.gunboards.com

- : Chart from National Library of Scotland

- : Based on Chart from National Library of Scotland

- : Based on Harwich Haven Authority Bathymetry

Notes and References

- 1The tugs were Dapper, Lady Brassey, Crested Cock and King Lear

- 2

- 3Another ferroconcrete structure

- 4collision with barrier see http://www.bobleroi.co.uk/ScrapBook/CityReunion/FortFanatics.html.

- 5See the account of George Tapper in BATES, MICHAEL. PRINCIPALITY OF SEALAND: Holding the Fort. 2015.

- 6Mines – see the account of George Tapper.

- 7

- 8Lights and Lighthouses were only lit under War Office instructions. “The principal keeper would receive a war office telegram telling them to exhibit the light on a certain night or nights between the hours of such and such. Right up until 30yrs ago we still held on station the war coverings for the lens which only allowed the central bullseyes to be shown, thus reducing the magnification and therefore the distance the light could be seen. Offshore lights communication was by radio. UK Lighthouses | Facebook Bill Arnold.”

- 9The displacement of the Fort works out at 3300 tons, 126′ net length’x88′ beam ‘x11 ‘draught gives 3293 cubic metres x 1.03 tons per cubic metre.

Image Credits and Sources

- Tow-to-site: Photo from www.gunboards.com

- : Chart from National Library of Scotland

- : Based on Chart from National Library of Scotland

- : Based on Harwich Haven Authority Bathymetry