In the “Age of Sail” at sometime after seven bells in the forenoon watch a Meridian Passage observation of the Sun established that it was local noon. The officer taking the sight called “Twelve o’clock, Sir,” and the captain said, “Make it so,” This defined noon, the glass was turned, eight bells were struck, and a new watch party came on duty for the afternoon watch.

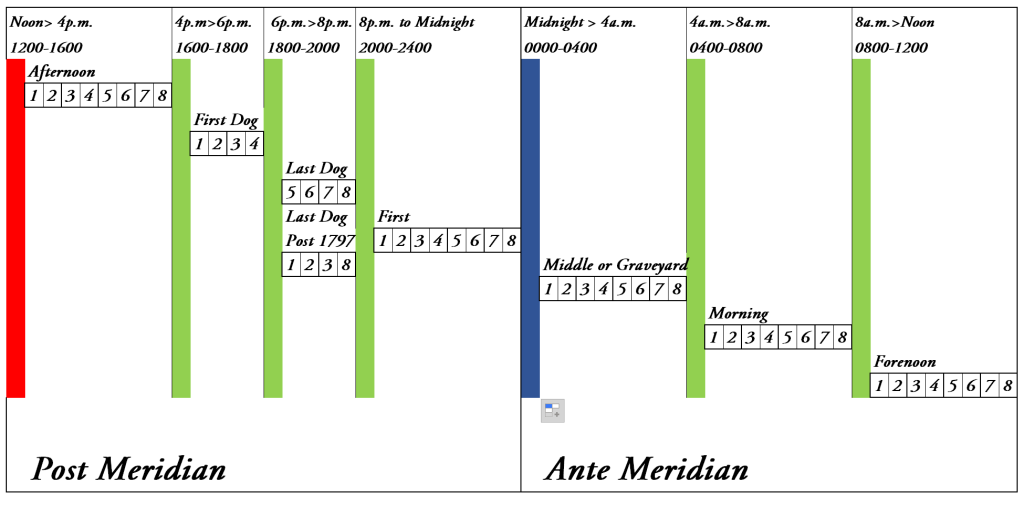

Watches allowed the crew to be rotated and rested in an efficient manner. A common arrangement was to divide the crew into Starboard and Larboard (Port) watches although there were sometimes three watches. Not all the crew belonged to a watch as this was not appropriate to everybody’s duties, these were the ‘wasters’. There were five, four-hour watches plus, to ensure that the crews’ hours varied from day to day, two two-hour watches completing the 24-hour cycle. The short watches were known as “Dog Watches”, perhaps because, being short, they were curtailed. With four-hour watches crew had only four or, at most, six hours off watch. Officers and Midshipmen fared better as they were usually on a three-watch system so could have eight hours clear. The Captain did not stand a watch1Masefield, John. Sea Life in Nelson’s Time. .

‘“So, the dog-watches are shorter than the rest,” says the parson, “very well. But why dog, if you please?”

As you may imagine, we looked pretty blank: and then in the silence the Doctor pipes up.

“Why, sir,” says he, “do you not perceive that it is because they are cur-tailed?”

-Patrick O’Brian – Book 8 The Ionian Mission 2Patrick O’Brian – Book 8 The Ionian Mission, ch.4, paragraph 100

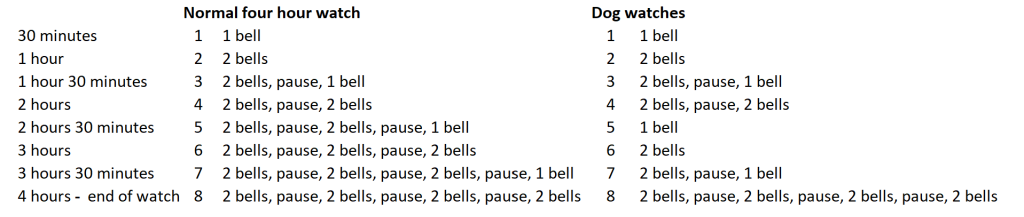

Time was reckoned by a timer glass which ran for thirty minutes. Sand ran through a restricted neck connecting two glass chambers and when it had all run into the lower chamber the time had elapsed. The glass was then turned by the Officer of the Watch and a sequence of bells were struck to indicate the passage of the watch. The glass was not as accurate or regular as a modern timepiece due to variations in movement, temperature, and humidity. However, provided that a Sun sight could be made then this variation could be managed over a passage. Sand timers have been used since ancient times, although the earliest recorded use at sea was in the fourteenth century. Originally these were likely to have been interconnected bottles containing sand which developed into the formed hourglass as glassblowing improved. For watch keeping the glass usually measured thirty minutes. From around the sixteenth century, there was a log glass with a period of around thirty seconds for measuring speed3Background on Marine sandglass (en-academic.com) 4Marine sandglass – Wikipedia .

Not all sailors were enthusiastic about completing their watch and as its duration was determined by the glass time could be shortened by subterfuge. One method was to ‘Flog the Glass’ by shaking it, another was to ‘Sweat the Glass’ using the warmth of the hand to expand the neck. This practice was discouraged5Sweating the Glass – Beat to Quarters .

Originally, the bell sequence was carried through the two Dog Watches so that the first ended at four bells and the second at eight bells. However, the mutineers at the Nore in 1797 used the fifth bell of the Dog Watch to as their signal to mutiny. As a result, the practice was subsequently altered on Royal Navy ships such that the sequence was one, two, three and then eight bells to mark the end of the watch. The use of pairs of strikes and pauses increases the intelligibility of the signal in a noisy ship.

The Nautical, Civil and Astronomical Day

From at least 1672 6See Nautical Time By Henry Harries , Mariner’s Mirror November 1928 until 1805 there were three days to reckon: the nautical, the civil and the astronomical. Each day system has its own logic. The correct system must be the Nautical Day because God says so:

And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day.

Genesis 1:5

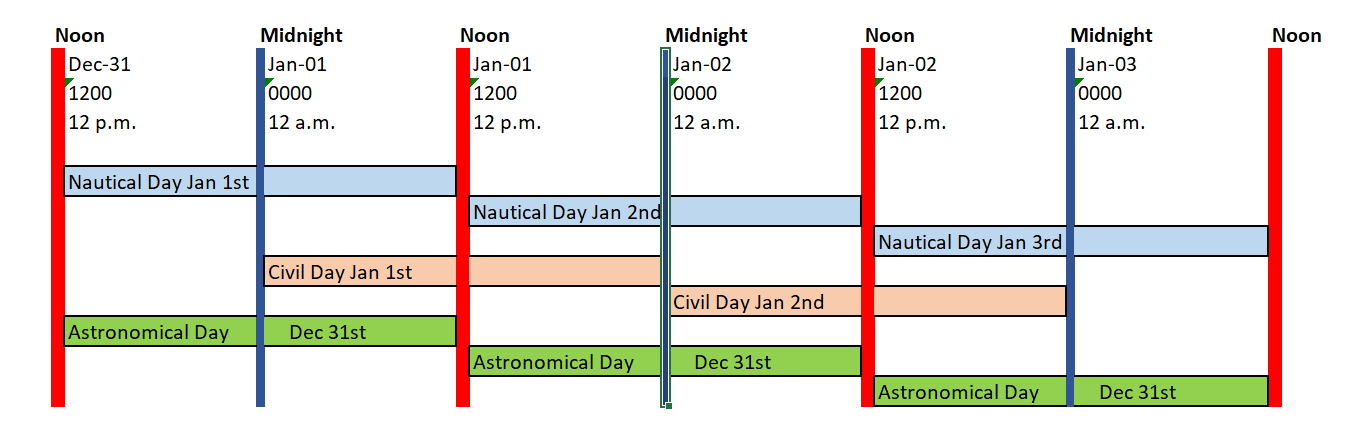

- The Nautical day is defined by the Meridian Passage of the Sun at noon (when the Sun reaches his highest altitude), and this is also when the position and day’s run can most conveniently be reckoned. This would not be easy at Midnight. From the Meridian Passage the next twelve hours were Post Meridian until Midnight and then Ante (before) Meridian for the final twelve hours of the day.

- On land it is not obvious when noon occurs so the Civil day would be confusing if it began then and it is also convenient to change day when most people are asleep.

- From the Astronomer’s viewpoint the Meridian Passage of the Sun is a perfectly sensible beginning to the day and to the counting of hours.

The nautical day entered in the log as Jan 1 began at noon of December 31st of the civil reckoning, and P.M. thus came before A.M. On the other hand, the astronomical day of Jan 1st began at noon of Jan 1st by civil reckoning and ending at noon on Jan 2nd. Consequently, the end of the nautical day, the beginning of the astronomical day and noon of the civil day, coincide7Explanation of the Ship’s Day vs Civil day. Also covers Date Line. .

Each method makes sense but, combining them provides an opportunity for confusion. However, ships’ logs show that suitable forms of words were usually found to avoid ambiguity although the change of Calendar in 1752 and crossings of 180° Longitude would have been challenging.

The instruction to change the reckoning of the Nautical Day in the Royal Navy to the Civil Day was issued on October 11th, 1805. This was just before the Battle of Trafalgar and Nelson’s death on 21st October although the order did not reach the fleet until after the battle8PEN & SWORD BLOG . This still left the Astronomical Day and the muddle was not finally resolved until January 1, 1925, when the ‘Astronomical Day’ was dropped from the American and British almanacs so days in the almanacs were now civil days as were the nautical days9History of the Nautical Almanac – Frank Reed – Date: 2012 Apr 9 .

Notes and References

A good explanation of watches here. on Historic Naval Fiction

More information on Bells in Wikipedia

Information on watch keeping systems.

- 1Masefield, John. Sea Life in Nelson’s Time.

- 2Patrick O’Brian – Book 8 The Ionian Mission, ch.4, paragraph 100

- 3Background on Marine sandglass (en-academic.com)

- 4Marine sandglass – Wikipedia

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8PEN & SWORD BLOG

- 9History of the Nautical Almanac – Frank Reed – Date: 2012 Apr 9