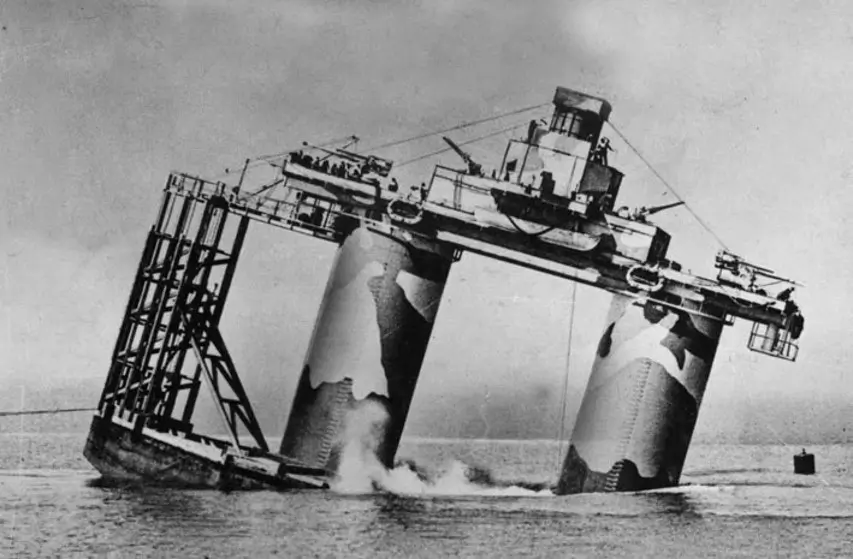

“Fort heeled over steadily to starboard and grounded on starboard fore quarter at about 30 degrees”.

positioning buoy, note the Dolphin.

Photo from www.gunboards.com

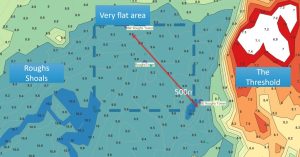

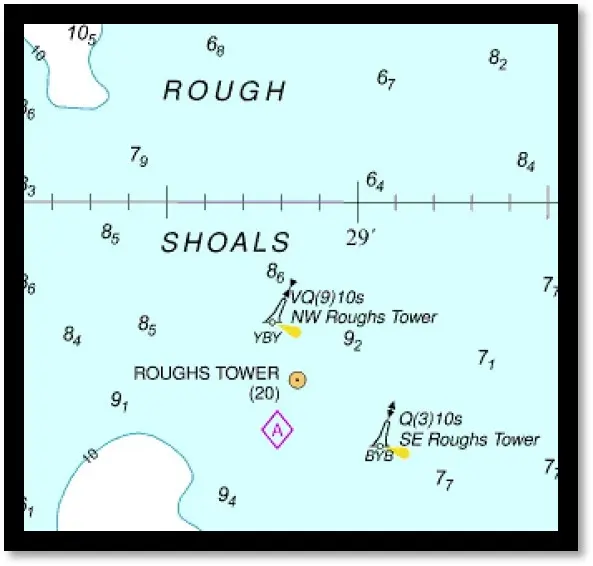

After the Fort’s unpleasant journey from Northfleet, it reached Roughs at 1600 on Wednesday 11th February. The plan would almost certainly have been to arrive around midday. In the selected area to the east of the Rough Shoals, the seabed is sand and pebbles and the bottom is flat with a slope of much less than 1% shown by the spot depths on modern bathymetry. The area was a good choice as it was a hazard to shipping and would be avoided.

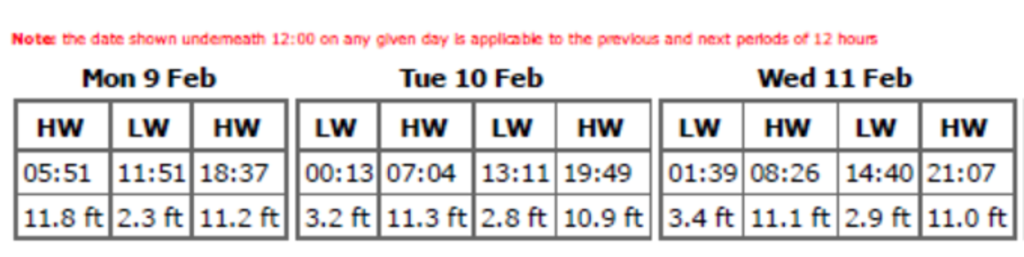

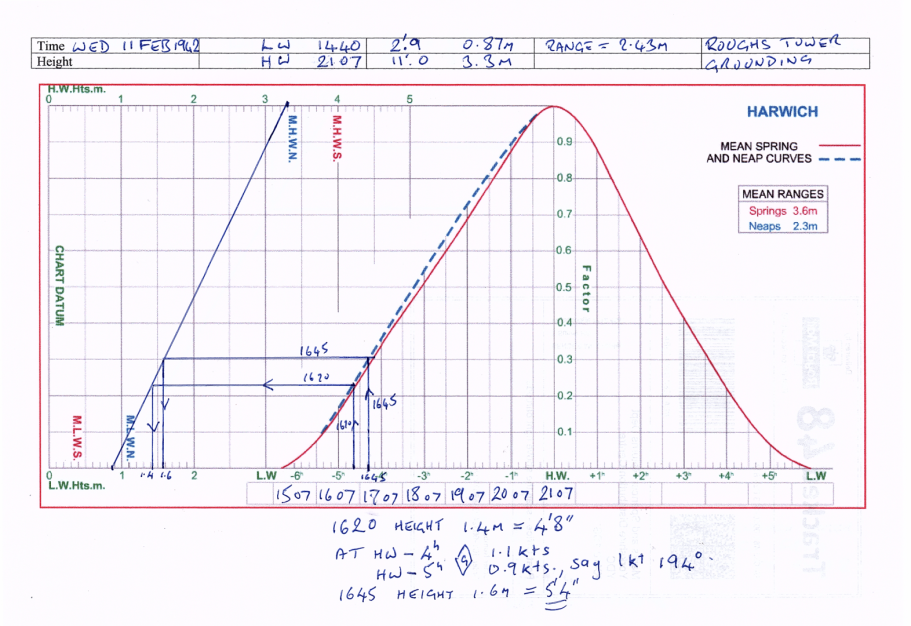

The Tides

The site was well buoyed to ensure the correct site was used. From Posford’s account, and judging by this later photo of Knock John, a line to an anchored lighter was used to maintain the position whilst sinking. One of the buoys would also have secured the telephone wire connected to the shore base, HMS Badger, at Harwich. The forts were probably only interconnected by radio. The tide would have been running south westerly at about 1 knot which should have drifted the fort about ¼ of a mile in the 15 minutes it took to sink had it not been secured.

The tides for the day were obtained from Easytide. A complication is that during the war double summertime was used so the times, in winter, are GMT+1. They had arrived after the flood had started but, surely planned to be there before slack water, around 1300. Another aspect of the delay was that the height of the tide would have been over 5 feet by this time. An increase of nearly 3 feet from low water and a lower was better.

The Felixstowe weather report gave a temperature just below freezing, dry, cloudy, hazy, and force one wind so probably nobody onshore would have seen the grounding.

The Sinking Plan

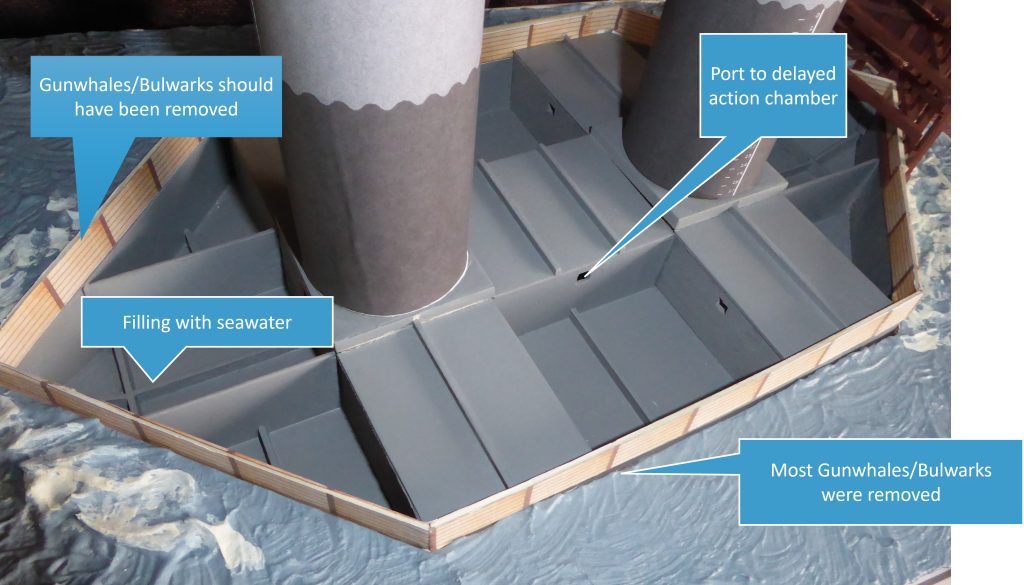

An ingenious arrangement of bulkheads, chambers and ports was devised to orchestrate the planned, graceful, submergence. Maunsell’s design was that, once the sea cocks were opened, for the concrete chambers to fill in an exquisitely choreographed automatic sequence.

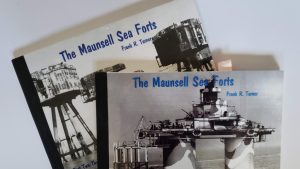

Correctly executed this would provide a safe and sedate grounding as shown here with the final Navy Fort U4 Knock John. This can be seen in the clip from the documentary by Frank Turner.

John Posford, who was to become Maunsell’s partner after the War, had arranged for a cine camera to record the event. Of local interest to Suffolk people is that his family home was in Falkenham near Felixstowe. However, it would soon be dark, and the Navy, who were in charge of this deployment, did not follow the plan. The video starts 8 minutes after the seacocks were opened.

An order came from the accompanying Warship to complete the operation immediately so perhaps matters were rushed. The gunwales on the port side were removed but rather than waiting until the starboard side had also been dealt with, the sea cocks were opened. There may also have been some excess water in the starboard centre chamber from the problems overnight. The accounts are classic British understatement:

“Fort heeled over steadily to starboard and grounded on starboard fore quarter at about 30 degrees”.

Posford’s account is similar:

“the descent, although perfectly safe, was not graceful”.

Look for the gunwales at the left of the pontoon and the men on deck. The Dolphin is at the southern end. Extracted from Frank Turner’s BBC(?) documentary on YouTube.

On the Seabed

Hopefully, the officer responsible was not Lt Notcutt RNVR who was the captain of the fort. He had been involved in the commissioning and was soon to move on to do the same with U2 Sunk Head Fort. Was he from the Woodbridge garden centre family? The 30-degree tilt must have been more than exciting for the sailors on the gun deck. However, Maunsell had done his sums and knew that the fort would not capsize. The fort then settled gently and was, for practical purposes level. On later deployments, the sinking was left to the engineers. This was sensible as sailors are meant to keep things afloat rather than sink them.

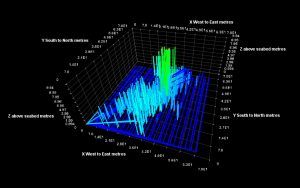

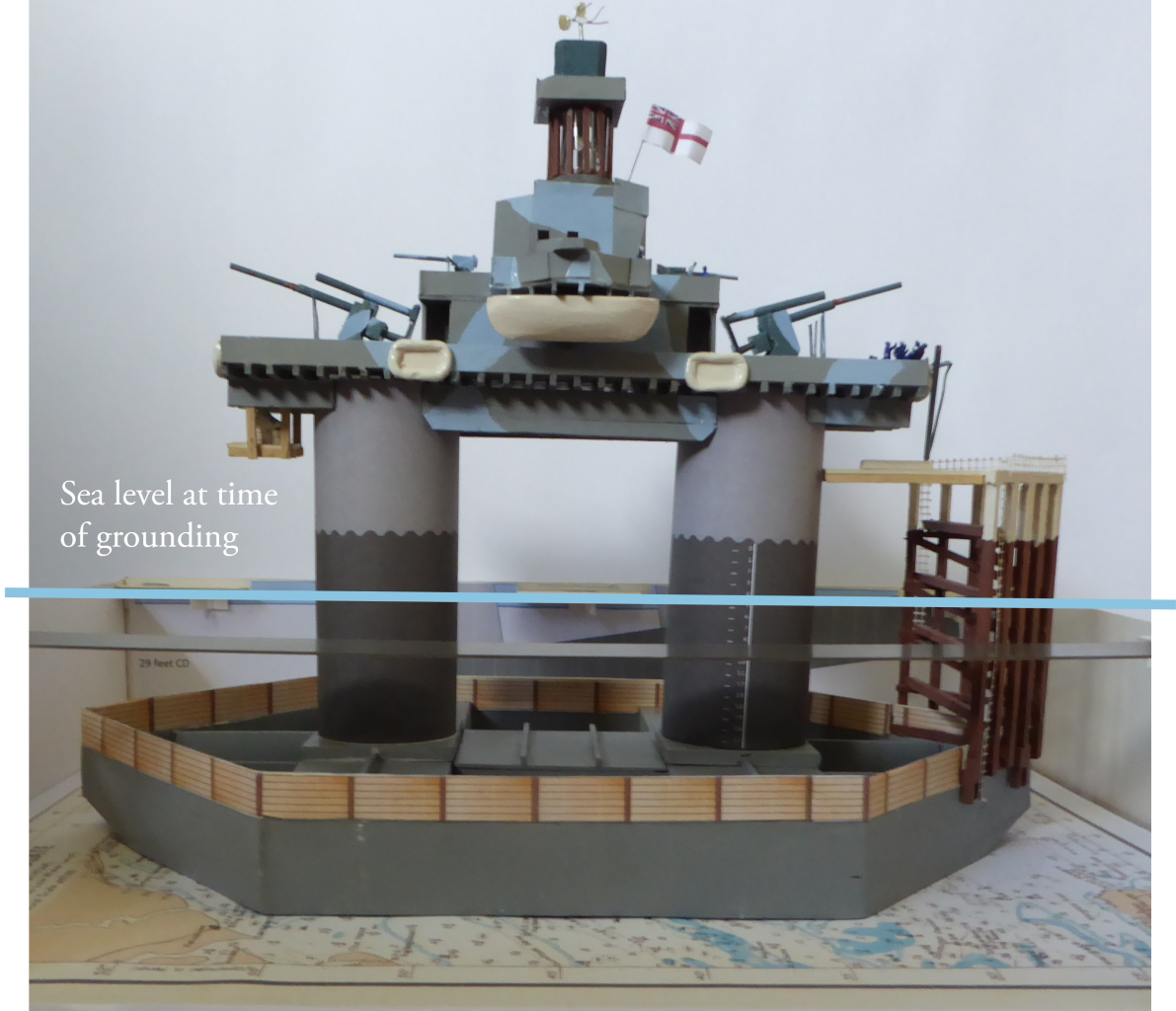

Understanding the grounding was part of the reason for building the model. Viewing the scene side on the sea the depth is small relative to the fort. Maunsell knew that as the fort touched bottom, even if tilted, the bows would form a pivot point and the buoyancy of the towers would turn the fort upright. This is where the extra depth could have been an issue. Later forts had a crushable concrete buffer on the bow to absorb the impact.

The Charted Depth today, by my measurements, is 27ft and, as they worked on LWOST and not LAT as we do today, this agrees with the 28ft by the 1943 chart.

The predicted tide height was 5ft at the time of grounding. The fort settled in 37 ft. which less 5’ tide makes 32 feet and leaves 4ft unaccounted for. The Fort’s settlement into the seabed could be responsible for most of this difference and there may also have been some surge given the previous strong northerlies. The fort is almost exactly aligned with the tide at the grounding hour on 012-192 degrees.

Gunwales a Hazard

The wooden gunwales should have been recovered by the tugs, but it was deemed too rough to do this. That disagrees with the sea conditions in the video which were slight. Hopefully, the timbers eventually fouled the props of enemy vessels and not British ships. This successful deployment was due to clever design and good site survey and selection. The tug Challenge survives still, she did not tow Roughs but did work on the deployment of Sunk Head and Knock John.

Fort fans who are also sailors may have noticed that every Navy Fort sits on a Tidal Diamond. This is no coincidence as the sites were carefully surveyed for selection and that data was used on later charts. The reason for the precise tidal information was so that the pontoon would have its long axis in line with the stream to prevent scouring which would lead to collapse.

There is also a correlation between tidal diamonds and old Lightship positions shown earlier which seems reasonable.

Rubble from London

In the days following the grounding several hundred tons of brick rubble, which was in good supply thanks to enemy bombers, were brought from London and dumped on the submerged pontoon to increase stability and reduce scouring.

The towers show the creative thinking, innovative engineering, and hard work of a great generation. The forts were produced quickly and cost roughly the same as a Lancaster bomber. They seem a better investment than our nearby, unused, 19C Martello Towers. Their success can best be measured by the deterrence they presented to the enemy rather than aircraft shot down.

Next Section The fate of the Navy Towers is covered here

Notes

Easytide Prediction for 9th Feb 1942 for Harwich, +1 for DST as double summertime in war.

Show-Prediction-enhanced-HARWICH-09_02_1942-for-7-days-EasyTide-printer-friendly-1Footnotes

Image Sources and Credits

Image Credits and Sources

- Fort-heeling-over: Photo from www.gunboards.com but probably J.Posford or Royal Navy

Image Credits and Sources

- Fort-heeling-over: Photo from www.gunboards.com but probably J.Posford or Royal Navy