The Allied invasion of France in 1944 was perhaps the largest, most complex project ever attempted. One of the many elements, Operation Fortitude, begun in early 1943, was a grand deception to persuade Nazi Germany that the invasion would land at Calais, not Normandy1The deception was masterminded by Sir John Turner, Director of Works at the Air Ministry..

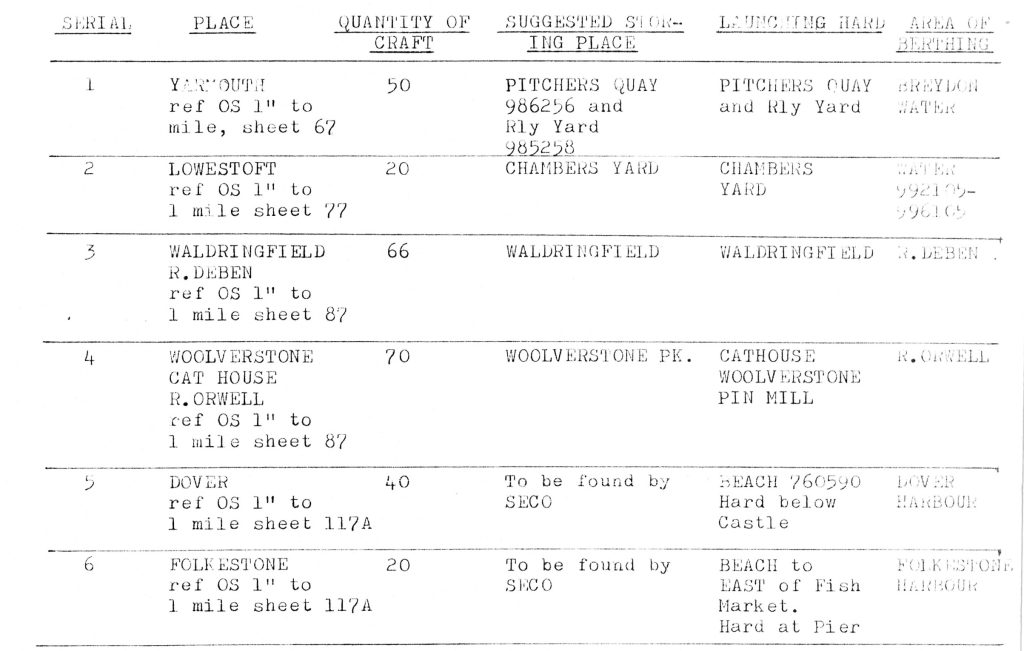

Southern England was to host the phantom First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG) under General Patton, with mock encampments and dummy landing craft moored on East Coast rivers from Yarmouth to Folkestone2Another part of the plan dealt with the North of the UK indicating an invasion of Norway..

The landing craft element was Operation Quicksilver centred on the rivers Deben and Orwell. Waldringfield, a village on the River Deben was key to this ‘ruse de guerre’, as was Woolverstone Hall on the Orwell. Quicksilver was but a miniscule part of Operation Overlord, one wonders whether today the same results could be achieved in the time.

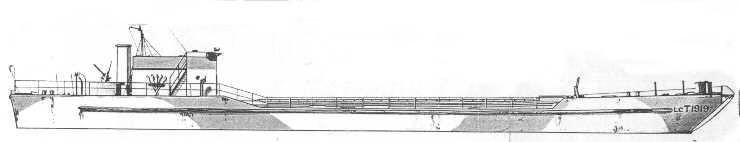

listed for sale in 2024 – similar in length and beam

to the fake MkIV LCT

Largest craft ever on the Deben

There were both real and fake landing craft of several types on the Deben in Summer 1944. The fakes were tank landing craft, the 34m Mark V and the larger 56m MkIV. Have there ever been larger vessels on the River Deben? Probably not, although the 1845 survey paddle steamer HMS Blazer, was close at 145′ (44m). The modern 53m long tanker in the photograph below is slightly smaller in length and beam than the Mk:IV: imagine dozens of these moored in the Deben.

Development of the Dummy Craft

The specification called for mock craft that, from a distance, would perfectly mimic a Landing Craft Tank (LCT) Mark V, there was a plan for the Mark IV as these were also deployed. They had to be assembled and moored in less than eight hours, the brief period of Summer darkness, and be suitable for deployment in estuaries in a force four wind.

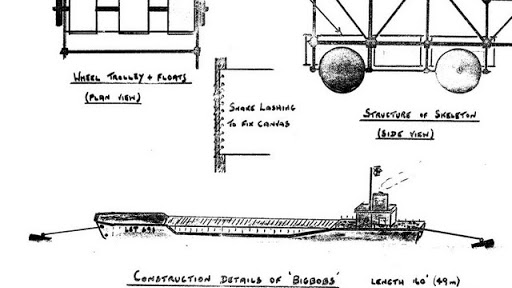

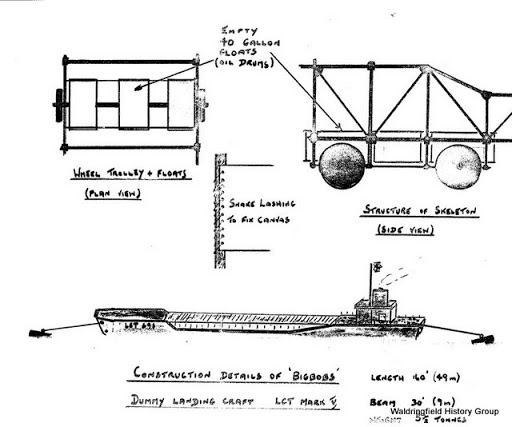

These craft were officially called Device 363Device 36 – reference for this lost. but were commonly known as Bigbobs. This was to distinguish them from the inflatable rubber dummy landing craft known as Wetbobs4Drybobs and Wetbob are terms used at Eton, this tells us something about the planners.5Some Wetbobs were moored on the Orwell but there is no record of them on the Deben.. The sketch plan provided by Peter Tooley shows how they were constructed6There is a discrepancy in in the dimensions on Tooley’s plan as the Mk V was actually 114′ in length with a 33′ beam (34mx9.8m)..

By late March 1943 work on prototype dummy craft had started and, by July, trials were underway on the South coast. The Royal Engineers considered the task did not need their skills so early versions were built by the Pioneer Corps. They would have to be assembled on site, quickly from a kit of parts.

Producing the kits

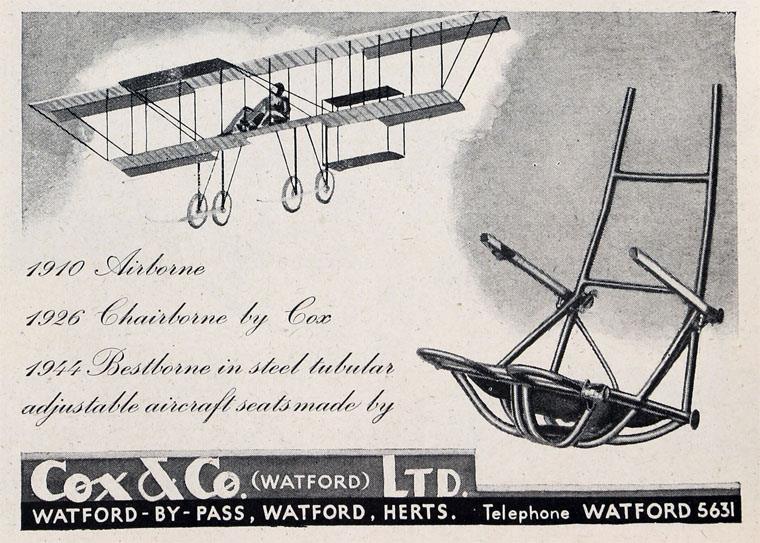

The engineering firm Cox of Watford, specialists in tubular steel furniture including wartime aircraft seats, was engaged for the production of the kits of parts and orders were placed in December 1943 for delivery in March 1944. The kits were manufactured with the cover story that they were mechanical elephants.

The Original Watford Memories and History Group

Each kit was made up of a frame of 3″ (75mm) steel tubes assembled on top of empty oil drums for buoyancy. The frame was covered by lace-up canvas sheets, that’s a lot of canvas, and crowned with a wooden wheelhouse. Roughly seventy forty-five gallon oil drums would be needed for flotation7Taking the weight of the kit at fourteen tons and dividing by 200 litre buoyancy of a standard oil drum..

Training the teams

In all, two hundred and sixty six8For context, the D-Day invasion involved around 3,000 to 4,000 Landing Craft which had to be moored and embarked along the English coast. Bigbobs were to be assembled and launched on the East Coast rivers during three weeks of Summer 1944, just before the invasion, this would require around seven hundred men.

The men needed training on how to build and deploy the Bigbobs, without error, in seven hours. Waldringfield was chosen as the training centre with the Maltings, the three-storey house adjacent to the Maybush Pub, as Headquarters9The Officer in charge of training was Captain Allen of the Royal Engineers.. Initially, men from the Worcestershire and Northamptonshire regiments were trained, with other units following. The courses started in February 1944 and, by the third week in April, training was complete. Working at night at that time of year would have been cold and sometimes wet. Officers were billeted at Mrs Turner’s Guest House10Deben House in Cliff Road with some men at the Maltings, although most were billeted in Ipswich due to the small size of the village.

Extra beer rations were provided for the Maybush, whose publican at the time, and many years afterwards, Albert Hill, was at HMS Beehive Felixstowe, a Petty Officer at the MTB repair base. As their training would have been at night, licensing hours may have limited the advantage the men could have taken from these rations.

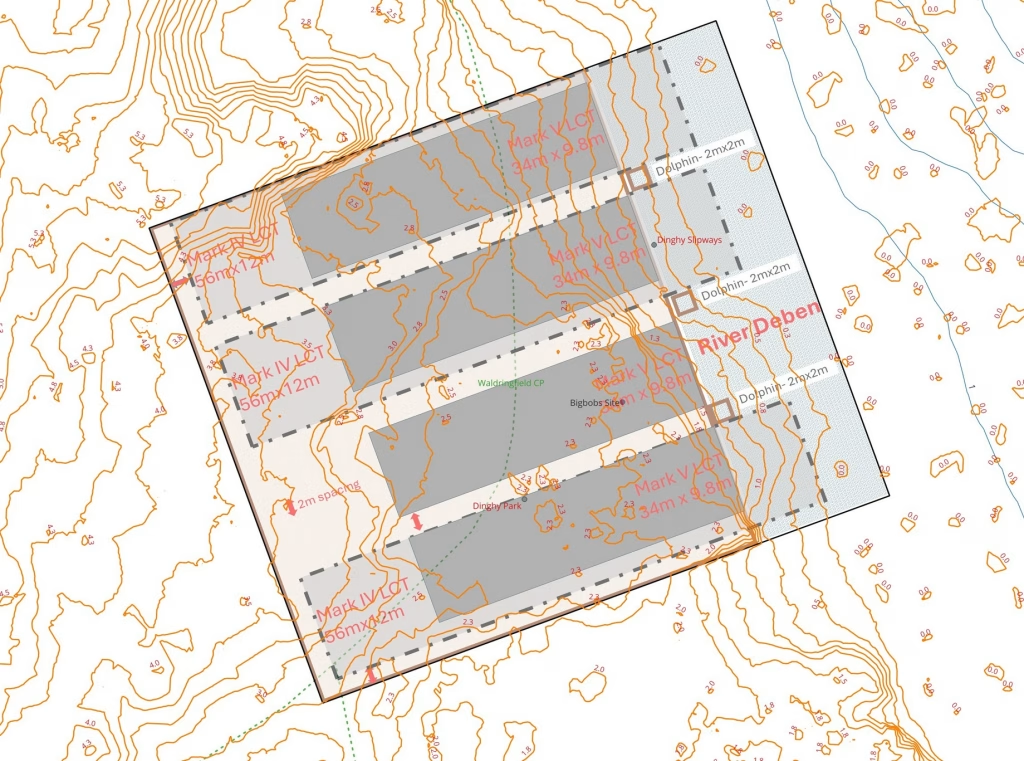

The construction site – a tight fit!

A construction area with access to the river was needed. Other than Felixstowe Ferry there is no suitable site, apart from Waldringfield, with both road and all tide access on the Deben.

The area chosen is now the sailing club’s dinghy park: beach huts were demolished or moved and the adjacent field to the West, Sedge Close, was used to store the kits. There is no easy road access to this area so possibly a temporary road11The route behind the beach huts was used in the late nineteenth century for moving coprolite to the shore, an alternative would have been to come across the fields from Mill Road, was built although there are no signs of it now.

Minor alterations of ground profile have been made since the War such as raising the level near the riverbank. However, unless there were major groundworks since 1944, the level part of the site would not have measured more than about 56m wide and 50m in depth12The 56m width assumes that the L shaped concrete wall was constructed post war.. It would have been possible to construct four MkV LCT dummies simultaneously as shown in the diagram although there would be little room to work with only 2m between the assemblies13Even then it must be assumed that there was working room at the northern edge despite the site not being flat there.. The notes section shows the modern contours in the area.

The much larger MkIV dummies were also constructed at Waldringfield since they appear on the Deben reconnaissance photograph14This type is not mentioned by Peter Tooley who was at Woolverstone but is mentioned elsewhere.. No more than three would fit widthways and, as they were most likely longer than the site at 56m15Length of site could have been a few metres more, the beach huts were removed and some changes to the level may have occurred., the bow section would have been rolled into the water so that the stern could be completed. The river end of the site would also have been wet at high water for the longer MkIVs further suggests this method.

A painting was made later in 1944 by a local artist, Ruth Waller16Ruth Waller- see here.. This shows two wooden structures and the remains of a third. These were most probably a form of Dolphin used to restrain the Bigbobs as they were rolled into the tideway. The spacing must have been carefully calculated to permit the launch of either four MkVs or three MkIVs.

Painting of Dolphins to add.

The construction schedule17Schedule from Operation Quicksilver by Peter Tooley. of four craft per night between May 22nd and 31st 1944, and three per night from June 1st to the 10th indicates that thirty-two smaller MkVs were built, followed by twenty-seven of the large MkIVs. This made a total of fifty-nine dummy LCTs which is seven short of the original requirement, the Orwell production was also short by seven craft.

The Hard

The hard constructed at Woolverstone on the Orwell, was for actual as well as dummy craft, it was larger, laid with flexible concrete mats18Woolverstone D-Day exhibition displays 8th-9th June 2024 and had wooden dolphins for securing the real LCTs whilst embarking, this would have been much more substantial than the flimsy ones at Waldringfield. The absence of these features shows that the Waldringfield site was only for construction and not meant to mimic an embarkation site: tanks would not have been suitable for the local roads.

The aerial photograph from 194819Aerial Photo – raf_58_103_v_5014 shows the site (zoom to the top centre near the beach huts), life appears to be returning to normal. Click here for photo 5014 if the space below is blank.

[Aerial Reconnaissance photograph from English Heritage, two zoom levels on some browsers]

The hards were not only functional but, as observed by Colonel David Strangeways when he took charge of Fortitude South, an essential part of the deception.

While provision had been made for the landing craft, nobody had given any thought as to how the notional troops were meant to board them. ‘They’d forgotten,’ Strangeways says, ‘to make any hards along the coast.’ ‘Hards’ were embarkation slipways. ‘Once I got going,’ he continues, ‘I said, “Oi, where are the hards?” And you daren’t make dummy hards, because if they are dummy, and spotted as dummy, better no hards at all. So they were made.’

Colonel David Strangeways20Colonel David Strangeways- From Joshua Levine, Operation Fortitude: The True Story of the Key Spy Operation of WWII That Saved D-Day (HarperCollins UK, 2011).

Now demolished.

from The Original Watford Memories and History Group

Building the dummy LCTs

Kits of parts were delivered in early May 1944 and stored under camouflage. Traffic in the village must have been heavy since delivering four Bigbob kits would require roughly eighteen three-ton trucks, from Cox at Watford, daily for nearly three weeks.

Working in the Dark

On the first evening of real construction, despite being well into May, the weather was chilly at only 7°C with a brisk northerly wind. The Bigbobs were assembled and launched between May 22nd and June 10th 1944. Each came as a five-hundred part kit which required a team of twenty to thirty officers and men, working for around seven hours in overnight darkness, to assemble and launch before dawn. At Waldringfield, the 4th Northamptonshire built the craft whilst the 10th Worcestershire were responsible for Woolverstone.

As three or four craft had to be assembled simultaneously, each had three groups of men working in parallel: one each on the bow, middle and stern/wheelhouse sections. Canvas sheets, pre-painted, were laced onto the tubular structure. The partially pre-assembled wheelhouse had to be lifted onto the 3.7m (12′) high deck: this involved a lift height of at least 6.5m (22′), so there must have been some form of mobile crane or gantry although working space would have been tight. There would have been no shortage of the 3″(75mm) tubes used to construct the craft and these would have at least 6m and perhaps 12m in length: these would be ideal for constructing a lifting frame (either ‘A’ or ‘n’ shaped). The wheelhouse could be assembled by the stern team and lifted into position before the hull was dealt with.

The design incorporated hinges so that, as the structure was rolled down the slipway on its forty-eight steel wheels to the water, the afloat portion would be horizontal whilst the remainder rolled down the incline. There must have been a risk of the structure twisting at this point, although the dolphins may have helped somewhat. The MkIVs were longer than the site so the bow and midships sections must have been rolled partially into the river so that the stern could be completed.

Launching the dummy LCTs

At the water’s edge responsibility transferred from the Army to the Royal Navy. As the dummy LCT was pushed by the soldiers into the river then a pair of, 10m (30′) long, LCVPs21LCVP – Landing Craft Vehicle, Personal (naval-encyclopedia.com) attached lines and started tugging. The shallow water, sticky mud and current must have been troublesome in the dark.

CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Positioning and mooring the Bigbobs had to be done rapidly, in darkness, regardless of wind and tide conditions and, with no hull or rudder in the water, course was managed by varying the thrust of the tugging craft either side.

The deployment of the craft could only begin when construction was complete, which would be just an hour or two before dawn. With between two and four LCVPs needed to position a Bigbob there must have been at least two, and possibly four, teams to deploy the four LCTs each night.

If construction was not complete by dawn, or there had been an unsuccessful launch, the whole assembly needed to be dismantled and concealed until the following night. Marks made on the ground had to be erased before daylight as these would arouse enemy suspicions so the ground was harrowed so that nothing untoward would be visible from the air. Similarly, all craft had to be moored before daylight since an image of one being towed would reveal that they were engineless and thus fake.

Two types of LCT on the Deben

According to accounts from the Worcestershire Regiment, who assembled the kits on the Orwell, there were two types of landing craft with the smaller being 114′ in length with a 33′ beam (34mx9.8m) and weighing thirteen tons22There is a difference in the weight of the kits: Tooley states 5.5 tons and the Worcestershire Regiment account says 13 tons. 23Thirteen ton is a more realistic weight for the kits. These dimensions are consistent with the Mk V. From the aerial photographs shown below it can be seen that there are indeed two distinct types on the Deben, although only one is visible on the Orwell photograph24There is a possibility that inflatable ‘Wetbob’ dummy Assault Land Craft were on the Orwell – see collision incident.. From the relative sizes the smaller craft are LCT MkV and the larger ones LCT MkIV.

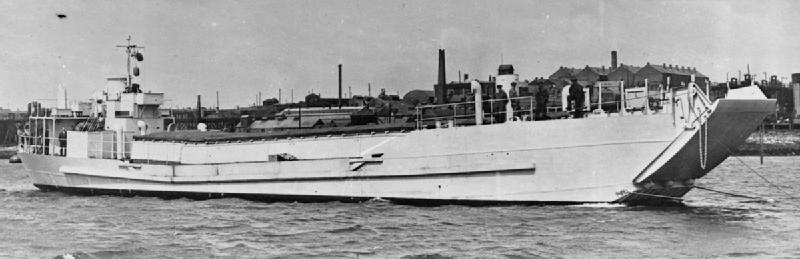

As the dummy craft were identical in size and appearance to the real ones the images below give an idea of scale. The MkV had a capacity of three fifty-ton tanks or nine trucks.

The significantly larger MkIV was on the Deben and there were, probably real, MkIVs moored there earlier on as well. The length and beam of the MkIV was 187’3″ x 38’9″ (56m x 11.6m). These could carry nine M4 Sherman or six Churchill tanks. The image is of a MkIII which was almost the same size as the MkIV.

Tim Sheerman-Chase, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

These landing craft, although dummies, are, quite possibly, the largest craft ever to have been on, or moored in, the Deben25HMS Kingfisher was the largest ship built on the Deben as was 110′ (34m) long. A Mk IV LCT was 56m..

Secrecy

As the real invasion of Normandy approached, draconian security measures were imposed. A one-mile-wide coastal exclusion zone was established from the Wash to Land’s End and, of course, this included the whole of Waldringfield: additionally, no civilian visits were allowed within ten-miles of the coast. Travel to Ireland was stopped, foreign diplomats were not allowed in or out of the UK and transatlantic telephone and radio communication was cut off.

Sailing barge crew detained

There was one incident on the Orwell regarding the deception: at night, nothing on the river was lit as it was wartime; when a sailing barge collided with an inflatable Wetbob landing craft, it became obvious to the crew that the vessel was fake. Consequently, the skipper and crew were detained by police until D-Day26Wetbob collision according to Joshua Levine, Operation Fortitude: The True Story of the Key Spy Operation of WWII That Saved D-Day (HarperCollins UK, 2011) 27Not, apparently, a Bigbob. This is the only mention found of the inflatable Wetbobs being deployed in the area..

Bringing the Dummy LCTs to life

Every effort was made to complete the deception. Crews were aboard in the daytime and smoke made from the funnels, Ensigns were flown, washing was hung out to dry and regular visits were made by tenders. Additionally there was regular radio traffic.

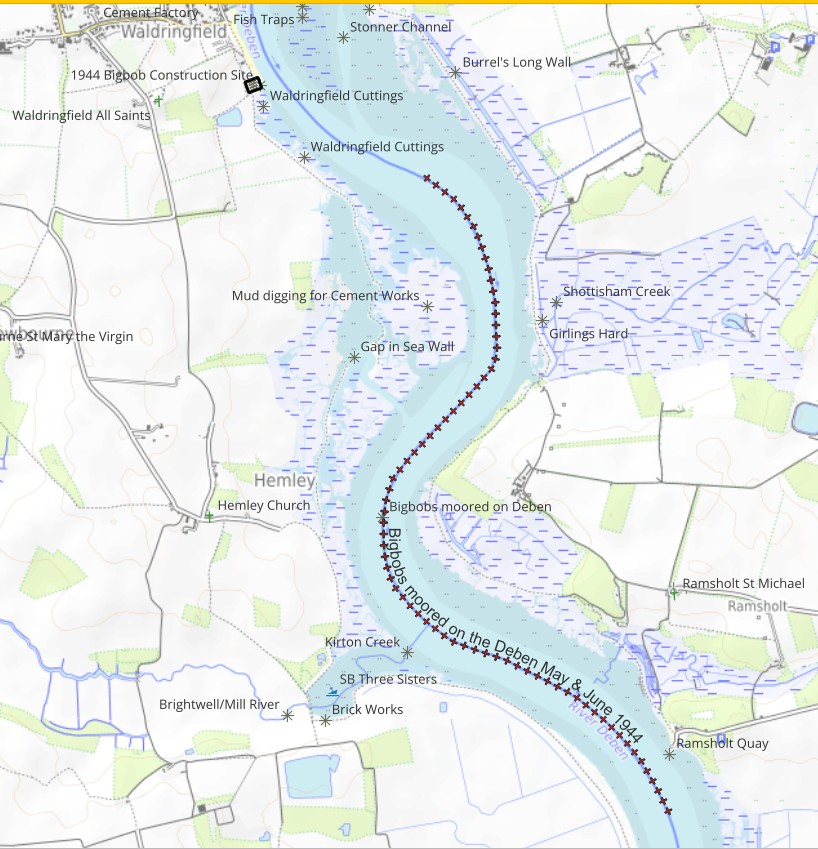

Mooring the dummy LCTs in the River Deben

The Deben’s fifty-nine28There were planned to be sixty-six dummy craft on the Deben. Bigbobs were the largest fleet, after Orwell’s sixty-three29There were planned to be seventy dummy craft on the Orwell.. They were built and launched over three weeks from in May and June 1944. Only one relevant RAF reconnaissance photograph (4006)30Aerial Photo – raf_106g_la_23_rs_4006, from the English Heritage Collection, has been located: this shows Bigbobs moored in pairs around Ramsholt on July 6th 1944. It can be seen that there are two distinct types of LCT. Click here for photo 4006 if the space below is blank – (The image can be zoomed.)

[Aerial Reconnaissance photograph from English Heritage, two zoom levels on some browsers]

As the deception was continued after D-Day then all the dummy craft would still have been in position when the photograph was taken. Calculation shows that the fleet of fifty-nine, moored in pairs, would have occupied about three miles of the river. If the moorings continued up the river, then they would have reached to Waldringfield sailing club. A member of the Ipswich Historical Transport Society who, as a boy alighted from the train at Woodbridge in 1944 recollected seeing some vessels downriver which were probably Bigbobs. Below Ramsholt was probably kept clear for real LCTs.

extrapolated from aerial photograph

Real LCTs on the Deben

These were not the only landing craft on the Deben in May and June 1944. On most days, real landing craft motored in stages from Great Yarmouth to Lowestoft and then to the Deben from where they sailed to Dover. These would have been moored overnight in Sea Reach near the Felixstowe Ferry. So, for almost a month, there were three or four dummy landing craft launched and moored, with a similar number of real ones arriving or departing. Co-ordinating all of this with the hours of darkness and the tidal entrance cannot have been easy, although, with only a 1.2m draught, the real landing craft could have crossed the Deben Bar before half tide.

Ensuring the deception worked

Test aerial photographs had revealed that the Bigbobs looked too good to be true, so they were painted with oil stains and rust to make them realistic. Once the Bigbobs were moored then the White Ensign was flown daily, smoke generated, laundry hung out and regular visits made by tenders to the skeleton crews on board.

There was intense signals traffic for the imaginary Army. This may have been in vain as it was subsequently found that enemy intelligence services were overwhelmed by the volume of information being collected.

Let the enemy know

Anti-aircraft gunners were given orders to fire at visiting enemy reconnaissance planes but ensure that they missed so that the images would arrive safely in Germany. What photographs were taken by the Luftwaffe is not known, maybe a search of the archives will find them31Archives to search see Archives of Aerial Images. One frustration was the lack of reconnaissance flights by them, for example there were none at all over Southern England between the 15th to 21st of May although, as deployment of the Bigbobs only commenced on the 19th or 20th, Operation Quicksilver was little affected.

This communication from Field Marshall Montgomery stresses the importance of the operation:

“Whilst it is fully realised that the launching and maintenance of the craft is an extremely arduous task, it is requested that every possible effort may be made to ensure that as much life and animation is given to the craft as possible. You should explain to all ranks that they are playing an extremely important part in the plan and that, in view of this, they are required to make as great an effort as Battalions deployed in the battle area.”

worcestershireregiment.com

The ruse continued

The Bigbobs were designed for only four weeks of flotation, but a request was made by Field Marshall Montgomery to extend their use to keep the enemy guessing and keep their troops at Calais. Consequently, efforts were made to keep the fleet in good order until the operation concluded in September 1944.

There were also fleets moored at Yarmouth and in the open waters of Dover and Folkstone. These latter had a far more difficult time and there were instances of craft having to be repaired or even scuttled in bad weather to maintain their authentic appearance.

What happened to them?

It is not known what happened to the fleet. Most probably the Bigbobs were towed back to the site and dis-assembled so that the materials could be re-used. It is conceivable that they were scuttled but, to avoid blocking the shallow, narrow channel, they would need partial dis-assembly which would not have been easy when afloat. Whilst this work could have been carried out in daylight it would still have been an undertaking comparable in effort to the original construction.

The outcome

Operation Quicksilver was a complete success with captured enemy records showing that they believed there to be 500 landing craft and forty two divisions in reserve whereas there were, only fifteen divisions and no landing craft available. On May 25th 1944, just before D-day on June 6th the German Commander in Chief, West still believed that the invasion would be between Dunkirk and Dieppe. Even on June 25th, he believed that the Anglo-American main force was uncommitted. The Germans did not move a division from the Calais area to Normandy until July 25th. This was a major contribution to the eventual defeat of the Nazis with Waldringfield and the River Deben playing their part.

Even more dummies

There were other dummy landing craft but made of concrete. These were built in Devon in order to train soldiers in embarkation and dis-embarkation on the beach. See here for more. Also, see Dummy D-Day Fleet on the Orwell, Woolverstone, D-Day at 80 Exhibition, and Ferro Concrete Barges postings.

This article is based upon ‘Waldringfield Threatens Hitler’ written for the River Deben Association Magazine Autumn 2010.

Notes

Notes on site, contours are AOD – 0m= Mean Sea Level, so high tide could be up to the 2m contour. Shifting the construction site a little to the south makes a better fit but is closer to the marsh.

P. Tooley’s plan describes an LCT Mk V – as 160’x30′ (49mx9m) with bridge/funnel assembly forward of the stern. Photos show that the bows taper inwards. That 49m length does not agree with Mk3 – 59m, Mk4 – 58m, Mk5 – 35m. Also, the aerial photos show two distinct types.

The possibilities are:

- Mark 3/III – LCT 7074 is a Mk III LCT – 192’x31′ (59mx9.4m)

- Mark 4/IV – This is a model of Landing Craft, Tank, Mk 4 (LCT Mk4) Scaled up model size is 192’X 40′ (58mx12). According to Landing Craft Tank (4) 980 – LCT (4) 980 they were 187 ft 3 long and 38 ft 9 in which nearly agrees so 56mX11.6m

- Landing Craft Tank (LCT) Mk4

- Mark 5/V – The LCT Mk V was 117’x32′ (35mX9.6m) with the bridge at the stern and bows which turn in sharply. This is a model of Landing Craft, Tank Mk 5 & LCT(5) scaled-up sizes of the model agree. LCT Mk 5– Landing Craft, Tank gives the size as 114’x33′ (34mx9.8m). The shape agrees with P. Tooley’s drawings so it looks like the smaller ones are MkV. The larger ones agree in shape with the MkIV.

- Specifications.

Measuring from the aerial photos; the larger craft are about 170×35= 4.83 L/B ratio and the smaller ones are about 115×35=3.29 L/B ratio. This is consistent with the larger ones being Mk4 and the smaller ones being Mk5. Consequently, it looks as if P. Tooley’s book has an error and also omits mention of the mixed types on the Deben..

According to worcestershireregiment.com there were two types with the smaller being 112ft by 35ft weighing 13 tons. This is consistent with the Mk V and suggests the larger ones were Mk 4.

The Deben aerial photo shows only 21 of the 66 Bigbobs. Of these 21 are the larger MkIV and 4 the smaller MkV.

Landing Craft Assault – much smaller 41 ft 6 in x 10 ft (12.65mx3.0 m) with shallow draught, for carrying troops. The Wetbob was the inflatable fake version.

Size of site: building four, smaller Mkv craft at 35mX9.6m would need a space of at least 37m deep and 47m wide. The larger Mk IV craft were 56mX11.6 which would need at least 58m deep and, assuming three built at a time, 40m wide. The above estimates allow very little working room. It is, of course, possible that the fronnt part of the assembly could be floated into the river whilst the centre and rear were built. This would reduce the depth of the site needed, but would be awkward. So the site should be at least 58m deep and 47m wide.

Lift height for MkIV wheelhouse, working from drawing (http://ww2lct.org/history/stories/lctevolution.htm) height of hull is 3.7m, wheelhouse excluding funnel is 2.5m: lift height =6.2m.

Mock Landing Craft at Braunton Burrows – US Assault Training Centre

Dummy landing craft, Dover Harbour

D-Day Landing Craft – new, to get

Has any research been undertaken into the sites at Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft?

Sources

Parts of the plan are described in ‘Operation Quicksilver’ by Sub Lieutenant Peter Tooley, the Royal Navy officer in charge of the construction team at Woolverstone32In 1995, he took a river trip on Waldringfield’s Jahan and, subsequently, wrote to the Boatyard with some details of the operation and enclosed sketch plans.. The Worcestershire Regiment account is another source as are RAF reconnaissance photographs.

10th Battalion Worcestershire Regiment – 1939-1945 – an excellent account, extract below:

There were two types of dummy craft, the smaller measuring some 112 ft. by 35 ft. and weighing 13 tons.

Although assembly differed considerably in detail, the main frame of both types consisted of specially manufactured tubular scaffolding, fitted with commercial oil drums for flotation, and covered with painted canvas to present an exact picture both to air and ground. Funnels, ventilators, chart boxes and other essential features were fitted during various stages of construction.

Craft were assembled on land and incorporated 48 sets of metal wheels enabling launching to be effected on completion. A skilled team of 30 Officers, N.C.O.’s and men could complete a craft in some 7 hours under good conditions in hours of darkness. Launching involved tides, tugs, wind, winch lorries, brain, brawn and a little luck.

By the third week in April approximately 600 Officers and men of each Battalion had received training, and it was not long before operation orders were received from 21st Army Group.

The 4th Northamptonshires were to be responsible for fleets at three sites on the East Coast. The 10th Worcestershire were to build, launch and maintain dummy fleets at Dover, Folkestone and Wolverstone, on the River Orwell, near Ipswich.

Detailed reconnaissance of sites began, bards were constructed, building areas were cleared and levelled (entailing the removal of thousands of tons of soil and two houses on the Marine Parade at Dover), and stores of all kinds began to arrive from factories and Naval and Military Depots. Under the orders of the Flag Officers in Charge, buoys were laid by the Royal Navy and fleets of small craft with their crews of Naval Ratings, Royal Marines, R.A.S.C. Motor Boat personnel and selected civilians were assembled with an eye to launching, towing, maintenance and animation when the operation proper began.

Peter Tooley, Operation Quicksilver (Romford, Essex: Ian Henry Publications, 1988).

ITV series “Anglia at War” from 1995

Joshua Levine, Operation Fortitude: The True Story of the Key Spy Operation of WWII That Saved D-Day (HarperCollins UK, 2011).

Decoy sites, wartime deception in Norfolk and Suffolk, H Fairhead

Suffolk’s Defended Shore: Coastal Fortifications from the Air. (excellent, available as free download).

This document The Green List of Landing Craft etc., which does not mention the dummy landing craft for obvious reasons, gives an idea of how amazing the D-day operation was.

Woolverstone FB post, another Woolverstone FB post giving an account.

Audio from IWM from Dame Marion Kettlewell.

Woolverstone personal account p.7

Wartime Deception in Norfolk and Suffolk by Huby Fairhead

Spotter’s Guide to Pillboxes & other anti-invasion structures of WWII.

Collection: Landing craft and landing ships

https://naval-encyclopedia.com/ww2/uk/british-amphibious-ships-and-landing-crafts.php

https://www.naval-history.net/WW2BritishLosses4Amphib.htm

The Boats that built Britain on Landing Craft – Youtube

Follow up sometime

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/1948921

THE TIN ARMADA: SAGA OF THE LCT By Basil Hearde

D-Day Statistics: Normandy Invasion By the Numbers

Met Office Daily Weather Reports for May/June 1944 see Felixstowe

Footnotes

- 1The deception was masterminded by Sir John Turner, Director of Works at the Air Ministry.

- 2Another part of the plan dealt with the North of the UK indicating an invasion of Norway.

- 3Device 36 – reference for this lost.

- 4

- 5Some Wetbobs were moored on the Orwell but there is no record of them on the Deben.

- 6There is a discrepancy in in the dimensions on Tooley’s plan as the Mk V was actually 114′ in length with a 33′ beam (34mx9.8m).

- 7Taking the weight of the kit at fourteen tons and dividing by 200 litre buoyancy of a standard oil drum.

- 8For context, the D-Day invasion involved around 3,000 to 4,000 Landing Craft which had to be moored and embarked along the English coast.

- 9The Officer in charge of training was Captain Allen of the Royal Engineers.

- 10Deben House in Cliff Road

- 11The route behind the beach huts was used in the late nineteenth century for moving coprolite to the shore, an alternative would have been to come across the fields from Mill Road

- 12The 56m width assumes that the L shaped concrete wall was constructed post war.

- 13Even then it must be assumed that there was working room at the northern edge despite the site not being flat there.

- 14This type is not mentioned by Peter Tooley who was at Woolverstone but is mentioned elsewhere.

- 15Length of site could have been a few metres more, the beach huts were removed and some changes to the level may have occurred.

- 16

- 17Schedule from Operation Quicksilver by Peter Tooley.

- 18Woolverstone D-Day exhibition displays 8th-9th June 2024

- 19

- 20Colonel David Strangeways- From Joshua Levine, Operation Fortitude: The True Story of the Key Spy Operation of WWII That Saved D-Day (HarperCollins UK, 2011).

- 21

- 22There is a difference in the weight of the kits: Tooley states 5.5 tons and the Worcestershire Regiment account says 13 tons.

- 23Thirteen ton is a more realistic weight for the kits

- 24There is a possibility that inflatable ‘Wetbob’ dummy Assault Land Craft were on the Orwell – see collision incident.

- 25HMS Kingfisher was the largest ship built on the Deben as was 110′ (34m) long. A Mk IV LCT was 56m.

- 26Wetbob collision according to Joshua Levine, Operation Fortitude: The True Story of the Key Spy Operation of WWII That Saved D-Day (HarperCollins UK, 2011)

- 27Not, apparently, a Bigbob. This is the only mention found of the inflatable Wetbobs being deployed in the area.

- 28There were planned to be sixty-six dummy craft on the Deben.

- 29There were planned to be seventy dummy craft on the Orwell.

- 30

- 31Archives to search see Archives of Aerial Images

- 32In 1995, he took a river trip on Waldringfield’s Jahan and, subsequently, wrote to the Boatyard with some details of the operation and enclosed sketch plans.

- 1The deception was masterminded by Sir John Turner, Director of Works at the Air Ministry.

- 2Another part of the plan dealt with the North of the UK indicating an invasion of Norway.

- 3Device 36 – reference for this lost.

- 4

- 5Some Wetbobs were moored on the Orwell but there is no record of them on the Deben.

- 6There is a discrepancy in in the dimensions on Tooley’s plan as the Mk V was actually 114′ in length with a 33′ beam (34mx9.8m).

- 7Taking the weight of the kit at fourteen tons and dividing by 200 litre buoyancy of a standard oil drum.

- 8For context, the D-Day invasion involved around 3,000 to 4,000 Landing Craft which had to be moored and embarked along the English coast.

- 9The Officer in charge of training was Captain Allen of the Royal Engineers.

- 10Deben House in Cliff Road

- 11The route behind the beach huts was used in the late nineteenth century for moving coprolite to the shore, an alternative would have been to come across the fields from Mill Road

- 12The 56m width assumes that the L shaped concrete wall was constructed post war.

- 13Even then it must be assumed that there was working room at the northern edge despite the site not being flat there.

- 14This type is not mentioned by Peter Tooley who was at Woolverstone but is mentioned elsewhere.

- 15Length of site could have been a few metres more, the beach huts were removed and some changes to the level may have occurred.

- 16

- 17Schedule from Operation Quicksilver by Peter Tooley.

- 18Woolverstone D-Day exhibition displays 8th-9th June 2024

- 19

- 20Colonel David Strangeways- From Joshua Levine, Operation Fortitude: The True Story of the Key Spy Operation of WWII That Saved D-Day (HarperCollins UK, 2011).

- 21

- 22There is a difference in the weight of the kits: Tooley states 5.5 tons and the Worcestershire Regiment account says 13 tons.

- 23Thirteen ton is a more realistic weight for the kits

- 24There is a possibility that inflatable ‘Wetbob’ dummy Assault Land Craft were on the Orwell – see collision incident.

- 25HMS Kingfisher was the largest ship built on the Deben as was 110′ (34m) long. A Mk IV LCT was 56m.

- 26Wetbob collision according to Joshua Levine, Operation Fortitude: The True Story of the Key Spy Operation of WWII That Saved D-Day (HarperCollins UK, 2011)

- 27Not, apparently, a Bigbob. This is the only mention found of the inflatable Wetbobs being deployed in the area.

- 28There were planned to be sixty-six dummy craft on the Deben.

- 29There were planned to be seventy dummy craft on the Orwell.

- 30

- 31Archives to search see Archives of Aerial Images

- 32In 1995, he took a river trip on Waldringfield’s Jahan and, subsequently, wrote to the Boatyard with some details of the operation and enclosed sketch plans.